Leadership

2020 Spotlight University of Maryland-College Park

As a campus situated in a community where almost one in four residents are immigrants, the University of Maryland-College Park (UMD) dedicated the 2018–19 academic year to exploring immigration, global migration, and the refugee experience. The Year of Immigration initiative led to more than 75 campus events, nearly 60 academic courses related to immigration, and extensive community engagement with local nonprofits, high schools, and community service groups. The initiative was jointly implemented by the Office of International Affairs (OIA) and the College of Arts & Humanities.

Against a backdrop of rising nationalism and a wave of anti-immigrant policies, international educators at UMD wanted to raise awareness of the issues affecting immigrants and refugees. In 2017, more than 300 international students and scholars at UMD were affected by travel bans implemented by the Trump administration. “That elevated my consciousness,” says Ross Lewin, PhD, associate vice president for international affairs. “I thought we needed to be more cognizant in recognizing that our international community is an extraordinary asset to the well-being of the university community.”

Creating A More Inclusive Campus

With a focus on issues such as immigration, forced migration, and the experiences of refugees, the Year of Immigration was created with a goal of expanding the notion of internationalization to cultivate a more welcoming and inclusive community. “Not only do we have 6,000 international students at the University of Maryland, and more than 1,300 international faculty members, we have countless numbers of international staff members who are working on our campuses every single day,” Lewin says.

After initially partnering with the School of Music in the College of Arts & Humanities, the OIA reached out to academic departments, other university-wide units, and undergraduate and graduate student governments. “The advantage of working with OIA was that because it is a central, campuswide unit, it could really give [the initiative] broad publicity and invite other colleges to participate in different ways,” says Bonnie Thornton Dill, PhD, dean of the College of Arts & Humanities.

The Year of Immigration boasted educational, cultural, and community engagement events and activities. For example, all first-year students read The Refugees by Pulitzer Prize-winning Vietnamese American novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen. Nguyen was invited to campus to speak as part of the College of Arts & Humanities Dean’s Lecture Series and also visited with students in individual Department of English classes. The School of Music also sponsored a yearlong festival featuring music and performances from around the world, such as the work of German American composer Kurt Weill. On-campus dining facilities also developed menus that included international cuisine.

Graduate student Anne Marie Shimko Corwith, who recently defended her PhD dissertation in international education, coordinated a three-hour Human Rights Day event in November 2018, with speakers who discussed efforts to support refugees abroad, barriers for refugees integrating into the United States, and the experiences of undocumented students at UMD. Corwith says that she personally has been able to continue working with several of the organizations that were involved in the event.

Professor Shibley Telhami, PhD, organized several events during the year that built on his own expertise as the Anwar Sadat Professor for Peace and Development. He organized a panel in March 2019, “The Global Response to the Refugee Crisis,” featuring Nancy Lindborg, MA, president and CEO of the United States Institute of Peace; Eric Schwartz, JD, president of Refugees International; and Her Excellency Dina Kawar, MA, the Jordanian ambassador to the United States. In addition, Telhami moderated a panel, “Immigrant Stories,” sponsored by the Carnegie Corporation, during which several immigrants shared their stories of coming to the United States. The panel included former UMD President Wallace Loh, PhD, who was born in China and then sought political asylum with his family in Lima, Peru, before coming to the United States to attend college.

Engaging the Local Community

The Office of Community Engagement focuses on connecting the university to the surrounding community. The office organized events for the Year of Immigration initiative, such as “Be Seen, Be Counted.” This event brought together nearly 60 nonprofit leaders, elected officials, government entities, business owners, designers, and members of the UMD community to learn how to apply a design thinking process to address hard-to-reach and undercounted populations in Prince George’s County and surrounding neighborhoods in advance of the 2020 U.S. census. The goal was to help stakeholders brainstorm ways in which they might better solicit participation from underrepresented populations in the census so that the resulting data would better reflect the county’s needs for public resources.

The Office of Community Engagement also launched Terps Translate, a project that recruited multilingual student volunteers to provide free interpretation and translation services of nonlegal materials at campus and community events. “The Year of Immigration gave us this outlet to highlight the importance of who our neighbors are,” says Gloria Aparicio Blackwell, MS, director of community engagement. “We don’t have to travel abroad just to learn about other cultures—we have [that opportunity] across the street.”

Dill says the Year of Immigration brought new focus to much of the work that was already being done in the College of Arts & Humanities. It also gave new impetus to the college’s global engagement requirement. All majors in the college must meet the requirement through language study, semester study abroad, or an individually designed experience that achieves the learning outcomes of the global engagement requirement. A number of courses from UMD’s Global Classrooms Initiative—virtual, project-based courses offered through OIA in collaboration with partner universities abroad—were also developed around themes related to the initiative. “The impact of the Year of Immigration on the college was to amplify the work we do, encourage its expansion, and build community connections and make them part of our ongoing curriculum,” Dill says.

Internationalizing With the Sustainable Development Goals

Since the Year of Immigration, there has been a renewed focus on expanding internationalization on the UMD campus. The OIA is currently developing a new international strategic plan that will be framed around the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In 2021–22, OIA is planning a themed year centered on SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities. This next themed year dovetails with the intended focus on inclusivity at UMD, emphasized by President Darryll J. Pines, PhD.

Reflecting back and looking ahead, Lewin says, “The Year of Immigration put wind at our backs and really distilled our own vision of how we want to advance internationalization at the University of Maryland moving forward.”

University of Maryland-College Park

2020 Spotlight DePaul University

When DePaul University, a private research university in Chicago, Illinois, switched to remote instruction in March 2020 in response to COVID-19, public policy professor Kelly Tzoumis, PhD, did not bat an eye. She was already prepared to teach the majority of her classes online, including a Global Learning Experience (GLE) course on environmental management in partnership with Henry Fowler, EdD, dean of graduate studies at Navajo Technical University (NTU) in New Mexico.

GLE courses are virtual exchanges between DePaul and partners in 29 countries. Tzoumis’s collaboration with the Navajo Nation is the first GLE course at DePaul that involves working together with another culture in the United States. During this course, all students took the New Ecological Paradigm survey, which explores how attitudes about the environment are shaped by underlying values, then compared and contrasted their results. The DePaul and NTU students’ answers differed significantly on questions about attitudes toward nature. DePaul students said they were first taught about nature in school before it became important to them. NTU students, in contrast, grew up with nature as part of their culture.

Because Tzoumis is training her students to become environmental managers, her goal is to guide them to think about issues such as environmental justice and culture. “I want them to step back and learn that how they view the environment impacts how they behave as managers,” she says.

Kassidy Simmons—a public service major at DePaul who says she did not even know Tzoumis’s class was a GLE course until she signed up for it—primarily interacted with NTU students through Zoom and email. “It was so interesting to hear about their lives, backgrounds, and educational journeys in comparison to ours,” Simmons says. “This is such a crucial time in history as well, and it was so eye-opening to hear how the Navajo Nation is handling everything with COVID-19 in comparison to how we are here in Illinois.”

While Tzoumis and Fowler initially considered canceling the course when the impact of the pandemic became clear, they ultimately decided to continue because of the unique opportunity it afforded students to collaborate cross-culturally despite the distance between New Mexico and Illinois.

Leveraging Expertise in Virtual Exchange

DePaul’s Office of Global Engagement, in collaboration with the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) and with the support of the Comprehensive Internationalization Committee (CIC), launched GLE as a university-wide virtual exchange initiative in 2013. The program has since been featured in the university’s strategic plan, “Grounded in Mission,” as part of the institution’s goal to “excel in preparing all students for global citizenship and success.”

Only around 4 percent of DePaul’s student body study abroad each year, so GianMario Besana, PhD, associate provost for global engagement and online learning, wanted to create more opportunities for global learning for students who do not participate in education abroad.

Since 2013, more than 2,400 DePaul students have enrolled in 155 GLE courses. Almost 300 faculty in nearly every discipline have participated in GLE training. Faculty members whose course proposals are approved by the CIC receive a $3,500 grant intended to facilitate travel for the DePaul faculty and their partner to collaborate in person.

Besana says he first heard about pedagogy for virtual exchanges around 2010 from Jon Rubin and his team at the State University of New York. It was a natural fit for Besana since he oversees both international education and online learning. Working with the CTL, Besana and his staff crafted a development program to train faculty in virtual exchange pedagogy. It supported DePaul’s missions of internationalizing the curriculum and creating international opportunities for students who are unable to travel. Now, DePaul has become a leader in the field of virtual international exchange, training not only its own professors but also faculty from other institutions.

The idea of virtual exchange has taken on more prominence this year since COVID-19 shut down most study abroad programs in March 2020. “I can’t tell you how many different institutions have reached out in the last 2 months saying, ‘How do you do this?’” Besana says.

But it is not just a matter of finding a partner and starting a collaboration. Faculty normally spend 6 months designing and preparing a GLE course, according to Besana. Professors at DePaul and the partner institutions work together to plan joint learning experiences for their students around specific learning outcomes through a variety of synchronous and asynchronous technologies. “It’s not something you can improvise,” he says.

Supporting Faculty for Successful Partnerships

During the first week of a GLE course, students engage in activities to get to know each other, followed by a content-focused phase typically centered around a collaborative project and a final period of reflection.

Each GLE course is developed in close collaboration between the faculty member and an instructional designer assigned through the CTL. “The support starts with faculty training followed by course-based instructional design support where we connect instructional designers with faculty to help integrate these global learning elements into courses,” says Sharon Guan, PhD, assistant vice president of the CTL.

The CTL trains faculty on topics such as intercultural collaboration and how to use English as a bridge across different cultures. The instructional designers then help faculty make sure they are creating assignments that are aligned with their learning outcomes and assess the global learning that takes place in the class. They also advise on the appropriate technology based on the needs of the partner institution. For example, Chinese partners have limited options due to government restrictions, while others might need to rely on low-bandwidth technologies, such as WhatsApp.

As director of virtual exchange and online learning, Rositsa (Rosi) Leon provides management and support for various aspects of DePaul’s GLE program across 10 colleges. In particular, she manages all GLE faculty grants and data reporting, as well as the quarterly project assessment process. She also facilitates the process of matching DePaul faculty with international counterparts and collects proposals from faculty who want to develop a new GLE course.

Leon says that pairing faculty for a GLE course has also been a way to deepen relationships with partners abroad. For instance, one long-standing partnership with São Paulo State University (UNESP) in Brazil has supported GLE courses, such as a robotics class in which students participated in online competitions via Zoom. DePaul has not only helped train UNESP faculty in virtual exchange pedagogy, but this GLE collaboration has also led to faculty visits and joint research. “This has really made the relationship stronger,” says Ana Cristina B. Salomão, virtual exchange coordinator at UNESP.

Leon adds that while the biggest benefit is for students, GLE courses promote ample professional development for faculty. “It provides opportunities for faculty to enrich their course content by including intercultural perspectives in their classes,” she says. “They are also learning new technological tools. We ultimately do it for the students, but there’s also a lot of support and growth for faculty.”

Balancing the Benefits of Virtual and Overseas Learning

Beyond the on-campus innovations sparked by GLE courses, a few faculty have also leveraged GLE components to enhance traditional faculty-led study abroad. In 2019, a DePaul professor who teaches a course on moral and ethical issues related to the bombings of Japan during World War II used a GLE course to connect with a partner at Nagasaki University before leading a program to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Inversely, study abroad programs have originated from existing GLE courses. A study abroad program on religion and globalization grew out of a GLE with Symbiosis International University in Pune, India.

Besana stresses that GLE courses are not intended to be identical to education abroad, despite their success in augmenting one another. In fact, GLE courses also offer opportunities to develop skills that students may not gain through traditional mobility. “Virtual exchange has some distinctive characteristics, including the fact that it helps students acquire virtual, global collaboration skills,” he says.

Associate professor Robert Steel, MA, who teaches postproduction film, has taught GLE courses with partners in Australia and Scotland. He says that the GLE courses are a perfect way to teach students how to work in the film industry, which frequently requires remote communication across borders. “I really want my students to have this experience because the film industry is so collaborative from beginning to delivery,” he says. “These global learning experiences teach students what it’s like to work in film production and postproduction.”

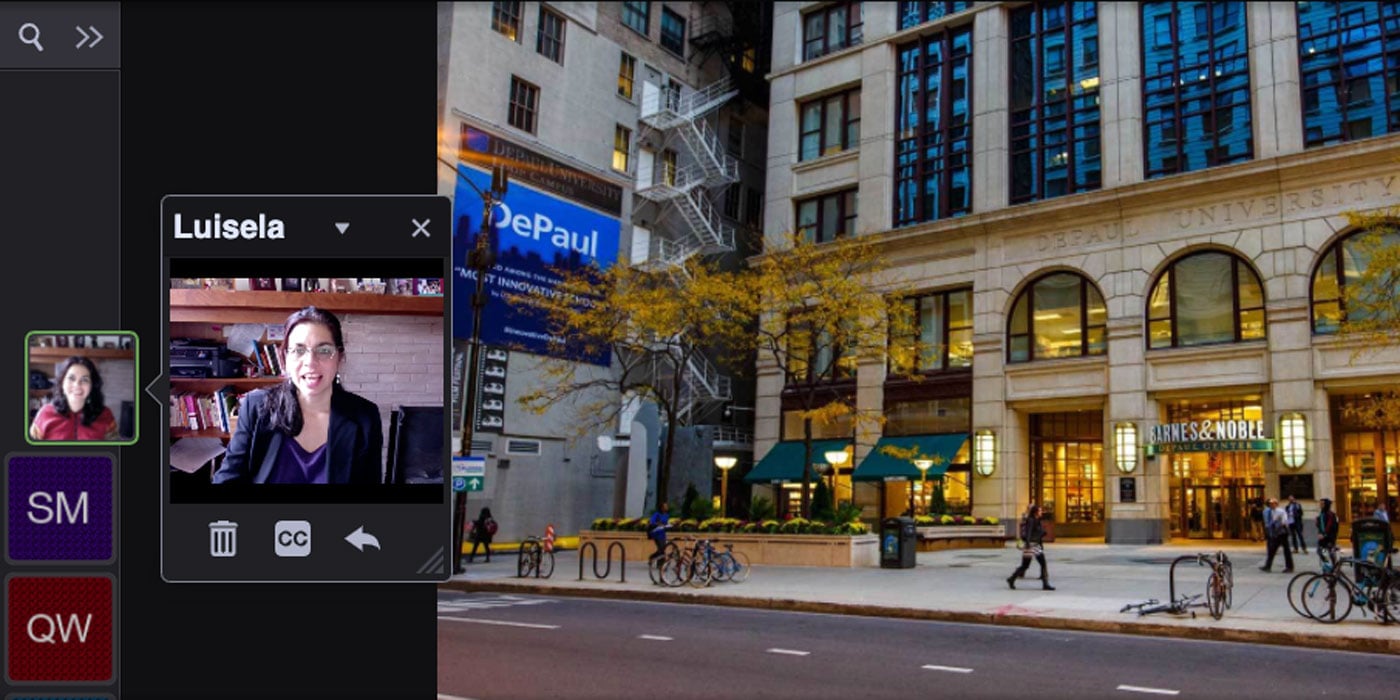

Media and cinema studies associate professor Luisela Alvaray, PhD, coteaches a GLE course on the history of cinema with a partner at the University of Zaragoza in Spain. “I want my students to have an awareness of other cultures,” she says. “Films are themselves carriers of cultural values. This has offered me an additional way to give my students that intercultural component.”

GLE courses also count toward some of the academic requirements for a new Global Fluency Certificate that enables students to demonstrate their achievements in global learning.

A survey administered at the end of each GLE course has consistently shown that students self-report growth in intercultural competence and virtual collaboration skills. For example, data collected from 92 GLE courses over 12 terms show that 70 percent of students agree or strongly agree that their GLE experience changed their perception of another culture or country, and 64 percent agree or strongly agree that the GLE course provided skills and knowledge that they would use in the future.

DePaul University

2020 Comprehensive University of California-Davis

Global Affairs at the University of California-Davis (UC Davis) works across disciplinary boundaries and promotes global opportunities for students, staff, and faculty. A commitment to sustainability—as well as diversity, equity, and inclusion—is woven throughout global learning, international student and scholar services, teaching, research, and partnerships.

As a major research university just 15 miles west of the California state capital of Sacramento, UC Davis has always been engaged internationally. In 2009, the institution won the NAFSA Senator Paul Simon Spotlight Award for its efforts to build connections in the Middle East and Cuba. When Ralph J. Hexter, PhD, became provost and executive vice chancellor at UC Davis in 2011, he wanted to expand the institution’s commitment to comprehensive campus internationalization.

“As I got to know the campus, I became aware of the tremendous number of engagements that were occurring all across the campus in international research and study,” he says. “It was really important to me that we have an office whose singular mission is to focus on the global.”

Hexter, who retired in July 2020, oversaw the establishment of Global Affairs in 2014 and brought on Joanna Regulska, PhD, vice provost and dean of global affairs, as senior international officer in 2015. With strong existing programs and enthusiasm across the university, Global Affairs has helped usher in a new era of global engagement at UC Davis.

When she first came to UC Davis, Regulska found a collaborative community ready to partner on a more comprehensive and accessible model for internationalization. “What we did is build up more expansive academic programs in order to serve and engage with the campus more broadly,” she says. “Building on what had already been done, we moved from an earlier definition of internationalization as mobility and individual faculty involved in research to seeing internationalization as advancing research, teaching, and service missions of the university.”

Strategically Growing Global Affairs

Under Regulska’s leadership, Global Affairs has brought together several different initiatives within the same building, the International Center, under two main pillars of units: (1) Academic Programs includes Asian International Programs, Faculty Programs, International Agreements, Partnerships, Visits, and the UC Davis Chile Life Sciences Innovation Center in Santiago; (2) Global Education and Services includes the Global Learning Hub (supports study abroad, study away, global experiential learning, and global leadership programs), Global Professional Programs (brings international fellows, leaders, and scholars to campus for professional development and collaboration), Services for International Students and Scholars, and UC Davis Arab Region Consortium.

Global Affairs has grown quickly—and strategically—since Regulska came on board. Since 2015, Global Affairs’s budget has increased by 115 percent to $18.3 million, and its team has grown by 40 percent to 78 full-time professional, academic, and student staff. Regulska created new positions, such as a dedicated communications director, an international agreements manager, and a travel security manager, which led to the first travel security policy among the 10 University of California campuses.

The results are tangible. UC Davis was a top producer of Peace Corps Volunteers in 2020, Fulbright U.S. Scholars in 2019–20, Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholars in 2016–17 and 2018–19, and Fulbright U.S. Students in 2017–18. Between 2014 and 2019, UC Davis also grew its international student population from around 4,000 to more than 8,000 international undergraduate and graduate students. In the 2019–20 academic year, the university had the 10th largest international scholar population and 18th largest international student population in the United States, according to the Institute of International Education’s 2019 Open Doors report.

UC Davis is one of 13 institutions in the United States that host the Hubert H. Humphrey Fellowship Program for young- and mid-career professionals. This program at UC Davis has convened 296 fellows from 105 countries focused on agriculture, rural development, climate change, and natural resource management. In addition, the campus has brought 99 fellows from 34 different countries in Africa to Davis through the Mandela Washington Fellowship for Young African Leaders.

Building Partnerships Across Campus

Centralizing Global Affairs into a single division has helped build connections across the UC Davis campus. Part of that comes from a recognition that many people will be referred to Global Affairs by other units, such as academic departments, the Office of Sustainability, or the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.

One way that Global Affairs is helping to break down silos across the campus is through its Global Strategy Advisory Committee, which brings together associate deans from all colleges and professional schools. The committee is tackling higher-level policy issues, such as developing guidelines for faculty who want to apply for Fulbright and other prestigious awards or establishing processes for international agreements and international delegation visits.

“We’ve done a lot to really standardize our agreement process and make it very legible and easy for faculty who are interested in bringing their collaborations to the next level with an official university agreement,” says Michael Lazzara, PhD, associate vice provost of academic programs.

Templates and step-by-step outlines of the agreement process are published on the Global Affairs website, which has allowed the university to better understand the range of partnerships with institutions abroad. “Whereas agreements were housed in different areas around the university in the past, we’re working to aggregate that data and bring it all together so we really have a full picture of all of the collaborations that are happening,” Lazzara added.

Beth Greenwood, JD, associate dean for international programs, represents the UC Davis School of Law on the Global Strategy Advisory Committee. She says that centralizing international initiatives under Global Affairs has been beneficial for everyone: “What we’re doing in the law school impacts Global Affairs, and what Global Affairs is doing impacts the law school. And working together, it really makes it possible to do more than we could do on our own.”

Promoting Global Education For All

After Chancellor Gary S. May, PhD, was appointed in 2017, international and global perspectives were woven throughout the new 10-year strategic plan “To Boldly Go.” Subsequently, a campuswide committee made up of representatives of every college and school, campus units, and students has been tasked with developing the first-ever global strategic plan to be completed during the 2020–21 academic year. The strategic plan will provide a guide for global strategies for education, research, diversity and inclusion, and partnerships.

“The charge of the committee is to formulate a campuswide plan on how to engage globally with the vision of advancing global good in California and the world,” says Fadi Fathallah, PhD, associate vice provost of global education and services and committee co-chair.

One of the areas of focus within “To Boldly Go” is Global Education for All, which aims to provide all UC Davis students—more than 39,000 undergraduate, graduate, and professional students—with a global learning experience before they graduate.

“The short story about Global Education for All is that we want all of our students to have an experience that’s global in nature, whether that be study abroad, research abroad, service abroad, work abroad, or having an experience here locally that connects them to another culture,” May says.

There are a number of reasons why students may be unable to travel abroad, including family and work responsibilities and finances. The COVID-19 pandemic has given new urgency to the idea of Global Education for All at a time when international travel is off the table.

The COVID-19 response has helped spotlight the possibilities for global learning via technology. “As much as COVID-19 is a terrible pandemic, this is a moment to realize how global learning is critical for everybody,” Regulska says. “We are improving accessibility to global learning by shifting away from mobility and thinking about other strategies we can use to provide global experiences for students.”

Hexter made the Global Education for All initiative a “provost’s priority,” which has signified the importance of this initiative and helped with fundraising across campus. Forty-two percent of UC Davis undergraduates are first-generation college students, and 38 percent are eligible for Pell grants. “We want to make sure that when we offer a program like this, students from every background can take advantage of it,” Hexter says.

Nancy Erbstein, PhD, associate vice provost of Global Education for All, added that global learning “helps cultivate a sense of community on campus, which we know is really key in fostering more equitable educational outcomes.”

The initiative includes academic programs, international and domestic experiential opportunities, and co- and extra-curricular activities related to global issues, systems, and perspectives. Local opportunities include, for example, a global living and learning community. The Intercultural Programs team also provides intercultural training workshops to different groups on campus who have an interest in global issues. Examples include a mentoring program for incoming international students and an effort to educate international students on the historical context for diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives.

Fostering Global Education in and Outside the Classroom

One of the ways UC Davis is encouraging faculty to include global perspectives in their courses is through its Curriculum Enhancement Through Global Learning program, through which more than 30 faculty from 25 different departments have revised their courses over the past 2 years.

As part of the Curriculum Enhancement Through Global Learning program, faculty participate in monthly workshops during the fall and winter quarters. Each faculty works on a syllabus and integrates global learning outcomes developed by Global Affairs. The three outcomes are (1) building global awareness, (2) engaging in cultural diversity, and (3) acting globally. A campuswide Global Education for All Steering Committee, which includes faculty, staff, students, and administrators, adapted the outcomes from the Association of American Colleges & Universities’s (2014) Global Learning VALUE Rubric.

“Our working global learning outcomes framework is a cornerstone of Global Education for All,” Erbstein says. “It reflects skills, knowledge, and understandings that we’d like students to develop while at UC Davis, because they’ll help graduates thrive in our interconnected world and collaboratively and equitably address global challenges.”

Aliki Dragona, PhD, faculty director of academic programs in the Global Learning Hub, teaches an upper-division writing class for students going into the medical field. She has been revising assignments to match them to the global learning outcomes. “How do you raise awareness? How do you encourage diversity? How do you encourage global action?” she says. “It has been a very productive and enriching experience to think globally about the curriculum that you’ve been teaching for a while.”

Guided by the internationalization values inherent to UC Davis’s mission, the Global Learning Hub coordinates study, experiential learning, and leadership opportunities abroad, in the region, and on campus. “The hub connects students to opportunities that include, but go beyond, movement of students around the world. The work we do is a holistic approach that provides learning regardless of location,” says Zachary Frieders, MA, executive director of the Global Learning Hub.

In addition to more than 50 different types of study abroad and hybrid programs, including quarter abroad programs and shorter seminar programs, the Global Learning Hub oversees in-demand internships in seven disciplines in 18 different locations, both in the United States and abroad. Students who are located at internship sites around the world take a two-credit online reflective course with a UC Davis faculty member, based on discipline, to provide deeper context through discussions, readings, and assignments and better link the work to the area of study and future career endeavors.

Erbstein’s hybrid program, Community, Technology, and Sustainability in Nepal, focuses on community and regional development. Students take part in virtual seminars throughout the fall quarter, and UC Davis students work in interdisciplinary groups with Nepalese peers to complete projects on topics such as sustainable agriculture, water resources, disaster reconstruction, food and nutrition, education, and public health. Over winter break, the UC Davis students travel to Nepal for 3 weeks. “They meet their Nepali counterparts, and go out to the community and meet their community partners, and work on their project implementation,” Erbstein says.

On campus, a new Global Learning Conference supports students in leveraging all types of global experiences to enhance their future academic or professional careers through workshops, career skill sessions, and networking.

Building A Sustainable, Global Framework

Another example of how UC Davis has implemented Global Education for All is the launch of a campus global theme inspired by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The inaugural theme is “Food for Thought: Feeding Ourselves, Feeding the Planet.” Global Affairs awarded small grants to 19 faculty from across campus for events and activities, such as documentary screenings and research projects on topics including nutrition, agriculture and economics, and education and ecosystems.

The Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing has received a grant to investigate how food can be used to treat iron deficiency anemia in high-risk immigrant and refugee populations. “We actually developed that as an active learning session into the curriculum under gastroenterology,” says Laura Van Auker, DNP, an assistant clinical professor of health sciences.

The SDGs provide a common framework for thinking about global problems and solutions that tie into UC Davis’s mission as a land-grant institution, says Jolynn Shoemaker, JD, director of global engagements. “Faculty are already really engaged in a lot of this work,” she says. “One thing that has been very valuable about this agenda is that it naturally links the local, regional, domestic, and international levels.”

Shoemaker adds that the SDGs support the university’s work in diversity, equity, and inclusion. “The SDG agenda is rooted in the concept of addressing root inequalities,” she says. “That really cuts across all of the work in different disciplines that is contributing to individual SDGs as well,” she says.

UC Davis Director of Sustainability Camille Kirk, MA, says that the SDG agenda also puts focus on the social and economic aspects of sustainability, not just the traditional idea of environmental sustainability. Global Affairs created an SDG internship in 2020 to provide students with the skills needed to address global challenges.

Anthropology and international relations major Christal Juarez is one of the first SDG interns. Her job is to help figure out ways that UC Davis can further engage with the SDG agenda. “As a first-generation student, I understand very clearly that not everybody has the opportunity to do things globally in a physical sense,” she says. “And so applying SDGs as a global framework is really important to give that opportunity to students. Because they can really innovate...while being in their own community in Davis.”

“One thing that is really blossoming here is the whole idea of helping students, faculty, and staff connect what they’re doing to global challenges...through the sustainable development framework,” says Robb Davis, PhD, director of intercultural programs and former mayor of the city of Davis. “It’s been really, really helpful to encourage people to talk about global challenges in the context of their own discipline.”

Engaging and Supporting Faculty and Staff

Efforts to further engage faculty and staff in internationalization include the Global Affairs Faculty and Staff Ambassador Program, which provides funding for faculty and staff to engage with partners, students, and alumni while they are abroad, and the Chancellor’s Awards for International Engagement, which recognizes faculty and staff who go above and beyond in their international engagement and efforts to help meet the goals of the Global Education for All initiative. A formal awards ceremony and networking event, known as International Connections, brings together hundreds of globally-engaged faculty and staff to recognize their work and spur future collaborations.

Faculty have also been able to leverage seed grants for international research as well as curriculum innovation and other global learning opportunities. They have offered a significant return on investment. “The seed grants have enabled faculty to raise almost 40 times the amount [we invested] in combined resources from other funding entities,” Hexter says.

Global Affairs has also been helpful in bringing together faculty from different colleges to collaborate on research projects. Ermias Kebreab, PhD, associate dean of global engagement for the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, says that Global Affairs runs a database that allows them to find colleagues who have relevant expertise. For example, he and his team were working on a grant application for the U.S. Department of Agriculture for a project in Kenya, and they were able to connect with other UC Davis researchers who work in Kenya. “It has a big impact in terms of us being more competitive,” Kebreab says.

Expanding Partnerships and Research Through Global Centers

One of the ways that UC Davis is extending its global reach and advancing mutually beneficial partnerships and research is through the launch of global centers in strategic regions of the world. The first global center will further existing partnerships in Latin America and the Caribbean by, for example, building on strong ties through the UC Davis Chile Life Sciences Innovation Center in Santiago. Founded in 2015, UC Davis Chile is cosponsored by the Corporación de Fomento de la Producción (Production Development Corporation).

The original collaboration was focused on the wine industry, says Lovell “Tu” Jarvis, PhD, executive director of UC Davis Chile Life Sciences Innovation Center. UC Davis has been able to partner in areas such as wine management, plant diseases, and irrigation. In addition, UC Davis researchers have started working with Chilean organizations on environmental issues. One project focuses on mechanisms to improve water quality in Chilean lakes, based on collaborative work done at Lake Tahoe in California.

Global centers have become a central part of the university’s internationalization strategy going forward. Building on an extensive network of relationships, UC Davis is expanding and enhancing collaborative academic and research opportunities as well as alumni connections around the world.

UC Davis is now looking to establish partnerships in other regions of the world, especially Africa, because a large number of faculty members are already engaged in research in African countries. UC Davis also has hundreds of connections with alumni of the Mandela Washington and Humphrey Fellowship programs. “Global centers enable us to have our expertise in various disciplines connected more directly to our colleagues in other parts of the world—and vice versa. We rely on connections and partnerships around the world to provide opportunities for our students, faculty, staff, and alumni,” May says. “Global centers also allow us to partner with local experts, communities, and institutions to build mutually beneficial collaborations.”

“Moving ahead, UC Davis is uniquely positioned to build upon past successes and continue connecting our entire university community to the world,” says Provost and Executive Vice Chancellor Mary Croughan, PhD, who was appointed in July 2020.

2020 Comprehensive Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University

As the world’s oldest university specializing in aerospace and aviation, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University (ERAU) traces its roots back to a pilot-training school founded in 1926. Today, the institution has residential campuses in Daytona Beach, Florida, and Prescott, Arizona, and an overseas campus headquartered in Singapore. A robust international student population, industry and academic partnerships around the world, and a strategic commitment to global engagement help Embry-Riddle achieve its mission to be a world leader in aviation and aerospace higher education.

When Kaloki Nabutola, PhD, was attending high school in his native Kenya, he would tell people that he wanted to study aeronautical engineering. A family member asked if he was planning to attend Embry-Riddle. He had never heard of the institution, but his interest was piqued when a friend asked the same thing. “I looked it up and found it had the number one aerospace engineering program,” Nabutola says.

Twelve years later, Nabutola has earned bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees from Embry-Riddle. In April 2020, he defended his dissertation in mechanical engineering—via Zoom due to COVID-19—with a focus on ground vehicle aerodynamics. “I’ve spent my entire adult life at Embry-Riddle,” he says.

Not only has Nabutola been a student at Embry-Riddle, he has also been at the front of the classroom as a graduate student instructor. He has been able to use examples from his own international experience when working with his students. “Being an international student has definitely diversified the way I think about engineering problems because I have seen them used in so many different ways,” he says.

Nabutola is one of more than 1,000 international undergraduate and graduate students who currently study on Embry-Riddle’s main campus in Daytona Beach.

Deepening an Early History of Global Engagement

Embry-Riddle’s history of global engagement began during World War II, when British pilots learned to fly alongside their U.S. counterparts. During the same period, the school also trained cadets from Latin America in aircraft maintenance at its site in Florida and established an aviation technical school in São Paulo, Brazil, in partnership with the Brazilian Air Ministry.

Now, the institution prepares its graduates for global careers in fields such as aerospace, applied sciences, business, cybersecurity, engineering, security, and space. “We’re an institution that has its history, soul, and mission all driven by aviation- and aerospace-related activities—not just airplanes, but anything that goes with the movement of people around the world,” President P. Barry Butler, PhD, says.

When Butler became president in 2017, it was clear to him that global engagement should be one of the institution’s five strategic priorities. He appointed a global strategy team focused on promoting global competencies among students, staff, and faculty; expanding Embry-Riddle’s global reach to new locations; and diversifying the university’s international student population. “A lot of our programs are built around knowing that every one of our students is going to be working in a truly global environment, whether that’s the airline industry, manufacturing, government, or being an astronaut,” Butler says.

Butler joined Embry-Riddle at a time when the institution was already in the process of consolidating its international initiatives under the International Programs division, which was established in 2016. “Until about 4 years ago, everything was decentralized from an international program perspective,” says Assistant Provost and Dean of International Programs Aaron Clevenger, EdD, who became Embry-Riddle’s first senior international officer in 2017.

International Programs currently manages international student and scholar services, international enrollment, international student programming, the Embry-Riddle Language Institute (ERLI), study abroad, and global engagement. International Programs also helps coordinate across the university’s two campuses in the United States, its campus in Asia, and more than 100 teaching sites on military bases through its worldwide campus.

The division has just finished its own strategic plan that integrates the objectives of the five pillars of the university’s strategic plan. “That was the critical piece….And tailoring what we are doing to the mission and vision of the institution meant that we’re all moving toward the advancement of the institution,” says Caroline Day, associate director of international experience and communication.

Creating the International Student Experience

In the past 10 years, Embry-Riddle has experienced a 57 percent growth in international students, who make up almost 17 percent of its student population and represent 110 countries. There are currently more than 1,000 international students at its main campus in Daytona Beach, and more than 200 at the Prescott campus. Daytona Beach also hosts students who come for flight training from the Singapore campus, which was established in 2011.

As the number of international students has grown, the university has focused efforts on helping members of this community integrate into campus life. Day coordinates international student orientation and cultural programming. She says her job is to make sure that international students are “safe, happy, and healthy and have what they need to be successful.”

In March 2020, Embry-Riddle moved all of its classes online in response to COVID-19. While some international students decided to return to their home country, many chose to remain on campus. The university kept a residence hall open for students who elected to stay, and International Programs staff reached out to all students who remained in the United States to make sure they were safe and had access to the services and support they needed. The office remained open and available to students, both virtually and with a physical presence throughout the pandemic; hosted monthly live info sessions about topics ranging from immigration to housing, COVID-19 safety precautions, and enrollment advisement; and designed a virtual engagement program.

Championing Aviation English

ERLI offers an intensive English language program for students who eventually want to matriculate at the university. The program has four levels, each with a special topics course that introduces students to relevant vocabulary and concepts for careers in aviation and aerospace.

The institution has also developed an innovative test, the English for Flight Training Assessment, as a requirement for all students studying aeronautical science. The assessment measures the aviation vocabulary and usage of students who want to become commercial pilots, ensuring that they meet the standards required by the Federal Aviation Administration to communicate with air traffic controllers and other aircrafts.

To support those who need extra assistance with their English, ERLI runs an aviation English language course in collaboration with the College of Aviation to help prepare international students who are going to become pilots. “As you can imagine, being able to communicate in the air is a little bit different from academic English and being able to talk about your paper with your professor,” says Hannaliisa Savolainen, MA, ERLI’s director.

Assessing and Expanding Global Learning Outcomes

In addition to exposing all of its students to new cultures through a diverse international student population, Embry-Riddle has worked closely with its Center for Teaching and Learning Excellence (CTLE) to internationalize its curriculum. One initiative is the development of seven student learning outcomes focused on global competencies that will be used to assess academic international education offerings, including education abroad, research abroad, and international internships. The learning outcomes were launched as part of an International Programs assessment for the 2020–21 academic year.

The learning outcomes have initially been integrated into education abroad offerings, but they can be applied to any course. “They have also been incorporated into the campus annual assessment process, meaning that they can be adopted by any department or course that would like to assess their impact on internationalizing the campus or providing global competency skills to students,” Clevenger says.

The next focus is to assess courses that are approved as part of a new global competence certificate that Embry-Riddle will launch in 2021. The curriculum is currently being mapped to the global competencies to determine the courses that will be included in the certificate, which is undergoing review by the faculty senate.

International Programs has also worked with the CTLE as it developed an inclusive teaching certification that introduces faculty to tools for successfully working with international students and helps prepare all students for global careers. More than 137 faculty have participated since the certification launched in 2019. Participants take part in workshops on topics such as universal design, how to manage difficult dialogues in the classroom, and how to teach in globally diverse classrooms. The certificate, which is recognized in the promotion and tenure process, is advertised by both International Programs and the CTLE.

Lon Moeller, JD, senior vice president for academic affairs and provost, says that one of the driving factors behind Embry-Riddle’s commitment to comprehensive internationalization and global learning outcomes is its deep engagement with employers and industry around the world. “We’re a really niche school in terms of aviation and aerospace, and these are industries that require internationalization,” he says. “We hear from our employers that they want Embry-Riddle students for their technical expertise, but they also really need to have that kind of broad worldview to be successful in the workplace.”

Embry-Riddle’s long history in aviation studies has positioned it to become a leader in aerospace, with degree programs in areas such as aerospace engineering, aerospace safety, space physics, and spaceflight operations. Space, the next international frontier, requires immense transnational understanding and willingness to work together, says Karen Gaines, PhD, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Embry-Riddle faculty and students across the university have even partnered with the International Space Station (ISS) and NASA to send payloads to the ISS.

Gaining Real-World Experience Through Study Abroad

Approximately 250 Embry-Riddle students study abroad each year, the majority through faculty-led programs. That number has drastically increased since 2011–12, when around 20 students per year participated in exchanges with international partners. Embry-Riddle was planning to offer 16 programs abroad during summer 2020 before they were canceled amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Many of Embry-Riddle’s education abroad programs focus on the professional application of skills and knowledge. Since 2012, William Coyne, EdD, a professor of air traffic management, has led a summer study abroad program to Europe focused on aircraft management. The group visits several air traffic control and related organizations, such as the regional International Civil Aviation Organization headquarters in Paris, the European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation (EUROCONTROL) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Brussels, and the European Union Aviation Safety Agency in Cologne. “We want to introduce students to the aircraft management world and how globally harmonized we are with our partners [around the world],” Coyne says.

Another popular faculty-led option is the annual business program to the United Kingdom, led by professors John Ledgerwood, MSA, and Tamilla Curtis, DBA. Each summer, participants visit British Airways headquarters at Heathrow Airport, where they are able to meet with representatives of different departments. They also visit various airports around the country to learn about aviation and airport regulations.

Clevenger says that one of the distinguishing factors of Embry-Riddle’s faculty-led programs is the opportunity to complete real-world projects that tie back to students’ majors. Examples include a program in Kosovo where students photograph cultural heritage sites using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), also known as drones, and a unique partnership that allows students to spend a week at Aegean Airlines headquarters in Greece. “The programs incorporate those aspects of study abroad that we know really drive home for students the importance of this global future that they are going to have,” he says.

Documenting Cultural Heritage in Kosovo

Embry-Riddle aeronautical science professors Kevin Adkins, PhD, and Dan Macchiarella, PhD, have taken students to the Balkans for a five-week summer program since 2016. Before this year’s program was canceled due to COVID-19, they had planned to take almost 30 students. At the start of this program, group members spend 1 week taking an upper-division social science class on Balkan history with a local professor while they tour Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia. Then, they spend 4 weeks in Kosovo, using the American University of Kosovo in Pristina as a base. They collaborate with Cultural Heritage Without Borders, a nongovernmental organization with a mission to help countries preserve important cultural heritage sites. Using UAVs, the group helps document cultural heritage sites in Kosovo, which was part of the former Yugoslavia.

After the breakup of the USSR, conflict between ethnic Albanians and Serbians led to a protracted war throughout the 1990s that resulted in NATO’s intervention in 1999. “The history of war since 1990 really affected the region. So we have a huge role in helping them reestablish themselves under a national identity,” says Macchiarella.

Unmanned aircraft systems are ideal to document sites because of the aerial perspective for the photography. Macchiarella says they are also particularly conducive to undergraduate research because they need a team to fly them. As students become more advanced, they can pilot the aircraft.

“It is work that is easy to scaffold,” Adkins says. “It doesn’t really take much training for a student to help clear an area or visually observe the airspace.”

The drones take thousands of pictures that can be processed and stitched together to make giant, highly detailed maps and 3D objects that can be manipulated. At the end of the program, the students give a project presentation that is attended by local officials, representatives from the Kosovo government, and U.S. embassy officials.

Ron White, who is majoring in unmanned aircraft system sciences, participated in the program in summer 2019. He says that being able to fly drone missions on weekends in several small towns was one of the highlights of the program. “This was an amazing opportunity to help local communities in the sense of documenting historic buildings, sites, and encroachment to these sites,” he says.

Architect Sali Shoshi, Cultural Heritage Without Borders’s executive director, adds that collaborating with Embry-Riddle has allowed the organization to both speed up a process that used to be very time-consuming and expand its reach. Three-dimensional models of cultural heritage sites can even be uploaded to games and online applications so that children and adults can explore them on their phones.

Collaborating With Aegean Airlines

Since 2016, Charles Westbrooks, MEd, associate professor of aeronautical science, and Mitch Geraci, MS, associate professor of aviation maintenance science, have taken students to Greece for a four-week summer program in collaboration with Aegean Airlines. They are also joined by faculty members in humanities and business.

A local travel agency, Get Lost, connected Embry-Riddle with executives at the airline who were interested in partnering with a U.S. institution. Get Lost Founder and CEO Angeliki Vaxevanaki designed a customized study abroad itinerary in which students sail in the Cycladic archipelago for 2 weeks, travel around mainland Greece for 1 week, and settle for 1 week in Athens, where they visit Aegean Airlines.

“Students get the chance to visit Greece, get to know the country on a deeper level, and understand its core values,” Vaxevanaki says. “Consequently, when meeting with Aegean executives, they are not only participating in workshops and providing solutions to issues supplied by Aegean, but [they get to] understand the company, its love for Greece, and its people.”

During the week spent in Athens, students receive briefings from key Aegean Airlines employees in charge of various parts of the company. Tours also include visits to Athens International Airport and a chance to fly on the flight deck of an Aegean A-320.

The students also work on projects developed through collaboration between the Aegean Airlines practitioners and ERAU faculty, Westbrooks says. Students have helped with projects such as developing a marketing plan targeted at Gen Z and designing the layout of a maintenance workshop.

David Morgan, who graduated from Embry-Riddle in December 2019 with a degree in aeronautical science, says that the hands-on experience of working with one of the top European regional airlines was “a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.” He is currently a flight instructor, teaching U.S. Navy personnel how to fly in a general aviation aircraft.

While he was in Athens, Morgan gave a presentation to Aegean employees about how to divert an aircraft to another airport if an issue arose with the flight. “Interacting with the CEO of Aegean Airlines, watching Aegean’s flight operation control center, and seeing maintenance personnel fixing aircrafts in real time tied together everything I learned about airlines at Embry-Riddle,” Morgan says.