Teaching, Learning, and Facilitation

2007 Comprehensive University of Oklahoma

A stranger visiting the University of Oklahoma’s graceful campus in Norman, Oklahoma, who drives down David L. Boren Boulevard, or strolls into the David L. Boren Honors College, or spies the statue of David Boren in a cornice on Evans Hall might assume that Boren led the university during its glory days.

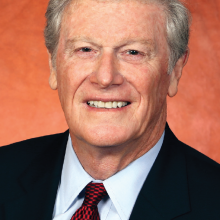

He did—and still does. For the University of Oklahoma, these past 13 years since David L. Boren relinquished a powerful seat in the U.S. Senate to lead his alma mater are the glory days. In writing a new chapter in a life of public service, Boren has presided over a period of dramatic growth and growing confidence for the University of Oklahoma. Sooners have always taken kindly to Boren, the former Rhodes Scholar and politician. They elected him governor at age 33 in a near landslide in 1974, and he won his last Senate race in 1990 with 83 percent of the vote. On his watch OU has quadrupled the number of endowed professor chairs, raised more than $1 billion, and erected dozens of new academic facilities. Even the powerful football team has added a seventh national championship to its trophy case. (A predecessor, George Lynn Cross, once quipped that he wanted to build a university of which the football team could be proud.)

Befitting a former chair of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and a man for whom a federal study abroad scholarship is named, Boren has given international education pride of place in OU’s curriculum and activities and made the Norman campus a regular stop for world leaders from Margaret Thatcher to Mikhail Gorbachev. Soon after taking office in 2006 as Africa’s first elected female head of state, Liberia’s President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf visited at the invitation of Boren and Ambassador Edward J. Perkins, OU’s senior vice provost for international programs and former U.S. ambassador to Liberia, South Africa, and Australia.

Spurt in International Studies

Oklahoma has boosted study abroad by providing $250,000 in international travel grants and fellowships for students and faculty; three-quarters goes to students. OU has added 15 faculty positions in Chinese and Arabic languages, Asian philosophy, history and politics, the economics of development, European security and integration, international business management, and other disciplines. The School of International and Area Studies, launched in 2001, has grown from three dozen to 350 majors. “It is a hard-charging group,” said political scientist Robert H. Cox, the founding director. “We require them to study abroad for at least a semester and take at least two years of a language.” Suzette Grillot, an associate professor of political science, says the myriad of international events held on the Norman campus “gets students energized. They learn something about the world here, and that energizes them to go out and actually see that part of the world or study the issue.” Perkins, who was ambassador to South Africa during the final tumultuous years of apartheid, says, “When we first started this, we heard from some professors, ‘Don’t be ridiculous. Anybody who wants to study international relations is going to go to some place back East to study.’ Well that’s not true at all.”

Of the 23,000 students enrolled on the Norman campus, 1,551 are international students. Oklahoma has forged exchange agreements with 173 partner universities in 60 countries and each year hosts approximately 750 visiting students while sending an equal number off to study at those institutions. Millie C. Audas, director of Education Abroad and International Student Services, notes that in addition to enriching the education of thousands of students, the exchanges also have produced at least 89 marriages. The ebullient Audas, a Bolivian-born former language professor with an OU doctorate in higher education administration, received a second doctorate in honoris causa from Université Blaise Pascal in Clermont-Ferrand, France—OU’s oldest partner—in 2005 for building Oklahoma’s exchange enterprise over nearly three decades. “I was honored not for any research, not for any academic advancement, but for the human relations and the human attachments between the people of France and the people of the United States. That was glorious for me,” said Audas, whose husband, William Audas, is a retired OU director of career services and founding director of the J.C. Penney Leadership Center at Price College of Business, in which numerous international students participate.

Audas first came to Norman as a language instructor in 1978. When she became the first full-time director of Education Abroad and International Student Services in 1986, she quickly found kindred spirits across the faculty, including cell biologist Paul B. Bell, Jr., who had done extensive research in Sweden and shared her enthusiasm for study abroad and partnering with institutions overseas. “By having all these exchanges, we have significantly increased the diversity of international students at OU,” says Bell, now vice provost for instruction and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Audas still travels the world to oversee existing exchanges and strike new compacts. “It’s labor intensive to make all these collaborations and agreements live. They are not just on paper. But we’ve had incredible momentum, rhetoric, and funding from President Boren,” she says.

Boren’s Days At Balliol

President Boren recalls with a smile that on his first visit to campus as president-elect, “Millie Audas intercepted me on the sidewalk and said, ‘Can I walk with you? I’ve been waiting all my career for someone like you to become president of OU.” Boren immediately proclaimed her his “soul mate.” Boren needed no convincing about international education. A congressman’s son, he was elected president of the Yale Political Union and won a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford after graduation in 1963. He was at Balliol College when word came that President John F. Kennedy had been shot; he was still there 14 months later when Britain bade farewell to its great wartime leader, Winston Churchill. “I learned so much about my own country by being outside it,” says Boren.

During Oxford’s long reading periods, he trekked to more than 30 countries across Europe and the Middle East. Boren also volunteered with the speaker’s bureau at the U.S. Embassy in London, speaking before ladies’ garden clubs in little towns across England. It left him convinced of the importance of being a good listener and seeing the world through others’ eyes. Boren believes it crucial for OU students to explore the world beyond the Red River. “Oklahoma is in the middle of the country. We have one of the lowest percentages of any states of first-generation Americans and the highest percentage of people born in this country,” he says.

OU Cousins

Soon after their arrival, Boren and wife Molly Shi Boren, a former teacher and judge, got into a conversation with a student from Malaysia who helped cater an event at the president’s house. “I said to him, ‘How many American students have you gotten to know really well while you’ve been here?’ and he said, ‘Not very many. We international students tend to stay together,’” Boren recalls. The young man expressed regret that he had not gotten to visit an American farm nor seen any “real cowboys.” The Borens’ offer to escort him to a friend’s ranch came too late; he was flying back to Malaysia in two days. “We felt terrible,” the president said. They decided to see to it that other international students would not miss such opportunities.

And so OU Cousins was born, a volunteer organization that matches U.S. and international students and arranges social outings and activities capped by a springtime barbeque with country music and line dancing in a big barn on a ranch outside Norman. “We tell everybody to dress up like cowboys and cowgirls. The international students really look like the part,” said Boren. The program, which started with 300 participants, now draws up to 1,000 each year. After the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, when Boren exhorted the campus community to make OU international students feel welcome, 1,600 students signed up. Other universities have borrowed the concept and even the Cousins name from OU’s friendship experiment, according to Kristen Partridge, assistant director of student life, who still corresponds with her “cousin,” a Singapore engineer she befriended as a sophomore in 1996.

Like many major universities with sizeable international student contingents, Oklahoma has a host family program called Friends to International Students that arranges for local families to invite students into their homes, take them grocery shopping and make sure they have a place to spend Thanksgiving and the winter holidays. Susan and Lyndal Caddell, Norman school teachers, have hosted students from more than a dozen countries on three continents, often several at once.

They’ve taken them to rodeos and the Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City, but the international students’ favorite outing is when the Caddells bring them to big family cookouts. “A lot go, ‘Wow! You have aunts and uncles and everyone else here, just like home,’” said Caddell. “It’s a lot different from the image of America they get from TV and movies.”

Getting Outside the Comfort Zone

In welcoming freshman, Boren always reminds them about the importance of “getting outside their comfort zone” and befriending OU’s international students. “Don’t ever let it be said that (a future prime minister) was in your class at Oklahoma and you didn’t know them,” he says. At every major academic convocation, a phalanx of international students bearing their countries’ flags marches behind bagpipers and the Kiowa Blacklegging Society, a group of Native Indians in feathered headdresses.

It takes an effort, too, for international students to breach their comfort zones. When twins James and John Akingbola of Lagos, Nigeria, enrolled as freshmen in 2003, they hung out at first only with Nigerians. When their older brother—who went to college in Britain and later earned a MBA at Purdue University—came to visit, “he wasn’t happy. He told us, ‘You’re not really maximizing your time here. Why don’t you just break out of your bubble and see what’s out there for you?” That was all the push they needed. James Akingbola, 21, became involved with the 150-member African Students Association and moved up the ranks of OU’s International Advisory Committee (IAC), which coordinates the activities of more than two dozen international student organizations. Akingbola, a chemical engineering major, was IAC president in 2006-07 while former IAC President Kenah Nyanat, a petroleum engineering student from Borneo, Malaysia, was elected president of OU’s student government. “I used to be very shy. I couldn’t speak to anybody alone. I depended on my twin to do the talking,” said Akingbola. “It’s so great to know different sets of people.”

The University of Oklahoma Alumni Association has gone international, too, recently adding clubs in Venezuela and Colombia to others across Europe, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. Jim “Tripp” Hall III, vice president for alumni affairs, calls the growth “astonishing.” In Moscow, alumni gather in the middle of the night to watch satellite feeds of OU football games, especially the annual showdown against the University of Texas. But in Brazil, OU alumni are more excited about the burgeoning international activities, Hall says.

Home of the Neustadt Prize

The University of Oklahoma is home to the prestigious Neustadt International Prize for Literature, a biennial, $50,000 prize bestowed by the university and its 80-year-old literary magazine, World Literature Today. The magazine also brings famous writers to campus for the Puterbaugh Conference on World Literature. Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk won the Nobel Prize a week after his 2006 visit. Between the Puterbaugh Conferences and the Neustadt Prizes, Norman regularly draws such literary lions as South Africa’s J.M. Coetzee, Japan’s Kenzaburo Oe, Poland’s Czeslaw Milosz, Mexico’s Octavio Paz, and Colombia’s Gabriel Garcia Marquez—all Nobel laureates.

Robert Con Davis-Undiano, an English professor who is dean of the Honors College and executive director of World Literature Today, says, “We’ve democratized the Neustadt program. It used to be a kind of ivory tower process, where the great writers of the world would come to campus and meet a few faculty.” Now, through classes, symposiums, meals and receptions, “upwards of 1,000 to 1,500 students are involved each time. We’ve really opened it up.” Davis-Undiano, an authority on Mexican-American literature, says, “When we brought in Kenzaburo Oe, for example, the Japanese students on campus were dumbfounded. They said, ‘In Japan, we’d get to wave at him in a parade. Here we get to have lunch with him.’”

Growing Connections with China

In 2006 the People’s Republic of China chose OU as the site for a new Confucius Institute, part of a worldwide network that encourages the teaching of Mandarin language and Chinese culture in schools and colleges. It will offer credit and non-credit courses to college students, business people and travelers as well as local school children, taught by OU instructors and teachers on loan from Beijing Normal University.

Boren took a personal interest in shaping an ambitious summer study abroad program called “Journey to China” in which students travel to Kunming, Shanghai, Xi’an, and Beijing for four weeks of classes on Chinese language, civilization, economics and politics. When Ming Chao Gui accepted a faculty position in 1994, there were just 14 students and he was the only instructor. “I was a one-man army,” he laughs. Gui was following in the footsteps of his late father, Cankun Gui, who taught at OU until his wife’s illness led the couple to return to China. In 2006–07, Chinese language courses drew 215 students and OU offered both a major and minor in Chinese.

Gui helped woo Sinologist Peter Hays Gries to Norman as the founding director of the Institute for U.S.-China Issues and as the holder of an endowed chair. The 39-year-old political scientist was born in Singapore and grew up in Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Beijing; his father was a U.S. diplomat. In fourth grade in a public school in the Chinese capital, he came in fourth in a citywide competition throwing hand grenades. “Of course, they were unarmed,” says Gries. “I guess because I grew up throwing baseballs and softballs, I had a knack for it that most of my Chinese classmates didn’t.” Gries speaks Mandarin with a Beijing accent. “It gives me a real advantage because people feel more comfortable with someone who speaks with an at-home accent,” he says. “It’s like a foreigner speaking with a Texas drawl.”

Gries has established a program to bring mid-level Chinese diplomats and their counterparts from the State Department to Norman each fall for an informal weekend retreat “to get to know one another outside the tense atmospheres in Washington and Beijing.” He explains, “crisis management is a huge problem in U.S.-China relations as recent history has demonstrated with the Belgrade bombing incident in 1999 and the spy plane collision in 2001. There just wasn’t enough familiarity between individuals in the two diplomatic services for them to be able to cut through the red tape and manage these crises in a productive way.”

Internationalizing the Community

Ambassador Perkins, who had led the Foreign Service and served as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations in addition to tackling some of the most difficult diplomatic assignments, says that when Boren wooed him to come to Norman, “he asked me to participate with him in bringing an international sphere” not only to the campus but also to the wider Oklahoma community. Like Boren speaking to garden clubs across England in the mid-1960s, Perkins found himself traveling around Oklahoma for speeches to Rotary Clubs and other civic organizations. “Community leaders in small towns throughout Oklahoma, whether it’s business or ecumenical or the YMCA or whatever, know about the International Programs Center,” he says. “They don’t know quite what it is, except to say, ‘They do bring some famous people here to Oklahoma—and they talk to us.’ I’m proud of that.” This spring, at age 79, Perkins stepped down as vice provost and director of the International Programs Center, but he will still teach one course a semester in the School of International and Area Studies. His successor as vice provost and holder of the Crowe chair is Zach P. Messitte, a political scientist from St. Mary’s College of Maryland.

Other OU leaders echo Perkins’ sentiments about the importance of educating not only the students but the local community about international affairs. Provost Nancy L. Mergler says, “The president really feels passionately about this ideal of creating the next generation of informed citizen who can sustain and build a community.” Seventy percent of OU students are from Oklahoma, and for undergraduates not bound for graduate school, “this is our opportunity to demonstrate to them how you learn about diverse ideas and come together and learn how to craft compromises. If you don’t have those skills, there really is not much hope for the future,” says Mergler, a psychologist.

Australian student Andrew Ballinger first came to OU in 2002–03 on an undergraduate exchange from Monash University in Melbourne to study meteorology. Ballinger originally intended to study at a British university, when a professor returned from a job interview and told him, “Do you know there’s a university in the middle of America’s Tornado Alley?” Ballinger adds, “I’d heard about the tornado hunters. For meteorology, that was sort of the dream.”

Ballinger, now 25, initially passed up college to get a commercial pilot’s license after secondary school. “I had a passion for flying, I was just flying anything in the air. And then I was teaching it and decided that I really loved the science behind it, especially the meteorology,” he says. “As a pilot, you’ve got to continually make decisions about the weather.” Ballinger, the son of dairy farmers, returned to OU in 2005 after graduating from Monash and now, with master’s degree from OU in hand, is off to Princeton University for a Ph.D. in atmospheric science and applied math. Norman, he says, “is an ideal base for an international student. I’ve been to 40 states so far as well as 30 countries after first coming here.” He’s interested in both the science and politics of climate change.

Intensive Arabic and a Blog About Syria

Another exchange program sends OU students to the Hashemite University in Zarqa, Jordan, for six weeks of intensive Arabic lessons each summer. Peter Wiruth, 22, of Tulsa, who graduated with honors in international studies in May 2007, says, “I gained as much in the six weeks as I had in the three semesters of classes here.” Wiruth was active in the Arab Student Association on campus, for which one of his mentors, Joshua M. Landis, assistant professor of Middle Eastern Studies and codirector of the Center for Peace Studies, serves as faculty adviser.

Landis, who was raised in the Middle East by parents who were academics, writes a blog on Syria that is must-reading for politicians, diplomats, and academics. It draws several thousand hits a day and is widely quoted by the news media. Its success shows “how much globalization and all the technology that goes along with it are globalizing universities,” says Landis. “I’ve been able to become part of the debate on Syrian policy.”

In addition to two-way exchanges, OU increasingly is sending small groups of students to study abroad with their professors during the summer. A Journey to Italy already has been added alongside the Journey to China—the president and his wife have attended portions of both programs—and summer Journeys to the Aegean (Turkey and Greece) and South America (Chile and Ecuador) are in the works. “My goal,” says Boren, “is to double and triple the number of students who have study abroad experiences.” Boren still serves on the U.S. selection committee for Rhodes Scholarships. Of the 42 applications he read last winter, 39 had studied abroad. “That just revved me up all the more,” he says.

‘A Totally Different Place’

Craig Lavoie, 23, of Bartlesville, Oklahoma, who graduated this spring with a degree in letters and political science and was a Rhodes Scholarship finalist in 2006, speaks admiringly of the way Boren uses the fundraising skills he honed during his political campaigns to raise millions now “for scholarships, endowed professorships, and new buildings and gardens. He’s going to leave an unbelievable legacy here.” Adds Lavoie, “I don’t even think I get the full scope of it. You talk to anyone who was here before he came in 1994, it’s just a totally different place.”

Joe S. Foote returned to his alma mater in 2005 and became dean of the Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communications. Once a broadcaster and press secretary to then-House Speaker Carl Albert, Foote was the founding dean of the College of Mass Communication and Media Arts at Southern Illinois University. He played a role in convincing former senator Paul Simon to come to the Carbondale, Illinois, campus in 1997 to launch a public policy institute that now bears his name. Foote, who has worked on journalism projects in Bangladesh as a Fulbright senior scholar and recently organized the first global congress of journalism educators, says it has been exciting “to return to a university so focused on the rest of the world. It’s much more challenging to become an international university in a land-locked state with no tradition of international dynamism.”

Kenah Nyanat, 22, the student body president, is a petroleum engineering student from the town of Miri on the island of Borneo in Malaysia. The eldest son of a Shell Oil Co. geologist who was one of the first from his village and tribe to attend college, Nyanat was a champion debater in high school and as a freshman emceed the Eve of Nations, the university’s annual celebration of international culture. He comes from a family of high achievers: sister Rami, 21, a sophomore studying geology, and her American OU “cousin” were named OU Cousins of the Year this spring for creating a multimedia scrapbook chronicling program activities. Both spent this past summer studying in China.

Nyanat has interned with energy companies in Houston and elsewhere and down the road envisions getting both a master’s degree in petroleum engineering and a MBA. “I really think President Boren has a plan on driving OU to the point where it is on the same level as perhaps an Ivy League institution, but maintain the same level of affordability that it has (now),” says Nyanat.

The end of OU’s international journey and David Boren’s tenure is not in sight. “We have so much more we want to do,” says the 66-year-old president. “I started a religious studies program so our students could learn about other religions and better understand what’s happening in the Middle East and other parts of the world. I’m looking to start an institute on the philosophical and cultural roots of the American Constitution.”

When he left the Senate, some colleagues were mystified, Boren says. Now, “a lot are jealous, frankly. This is where the action is, I tell them. I’m following my dreams.”

2007 Comprehensive Georgia Tech

Georgia Institute of Technology President Wayne Clough no doubt was half jesting when he told student radio station WREK an easy way to pronounce his name: “rough, tough, Clough.” But it also fit the robust, can-do image of the famed engineering school with the boisterous fight song in the middle of Atlanta. Georgia Tech was founded in 1885 by Atlantans hoping to push post-bellum Georgia into the industrial age. A shop building went up alongside the iconic, gable-roofed Tech Tower, and five shop supervisors were hired to work alongside the first five professors. For decades it was primarily an undergraduate institution, with a grand football team—the eponymous John W. Heisman was the first coach—and no alumnus more revered than golf legend (and mechanical engineer) Bobby Jones. It wasn’t until 1950 that Tech awarded its first Ph.D. In 2006, Tech awarded 400 Ph.D.s—two-thirds in engineering—along with 2,500 bachelor of science and nearly 1,300 master’s degrees. Some 2,700 of the nearly 17,000 students are international, and two-fifths of the 845-member faculty was born outside the United States. With national stature long achieved, Georgia Tech now wants to make its name as an international institution of higher education and research.

Georgia Tech’s immodest strategic plan lays out the ambition to become “a source of new technologies and a driver of economic development not only for Georgia, but also for the nation and the world…. We want to be a leader among the world’s best technological universities.” The journalist-author Thomas Friedman, in updating his best-seller The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the 21st Century, singled out for praise Georgia Tech’s ambitions for branch campuses on several continents and for giving its undergraduates deeper international experience. He praised Tech’s Clough for “producing not just more engineers, but the right kind of engineers.”

Clough has capitalized on opportunities to expand Tech’s global reach, starting with the 1996 Olympics, two years after his return to campus. “We realized the Olympics would be an opportunity” to advertise Georgia Tech “as a global institution,” he says. Georgia Tech hosted swimming and diving events and the Olympic Village; those residences now are dorms, and the Olympic aquatics facility an upscale student recreation center. Recently Georgia Tech acquired 2,000 more onetime Olympic Village beds from adjacent Georgia State University.

‘Just Like Buying a Coca-Cola’

Jack Lohmann, vice provost for institutional development and an architect of Georgia Tech’s ambitious International Plan (IP) for undergraduates, says it helps that Tech “is an entrepreneurial place.” On the international front, “we’ve got a lot going on, all the way from the traditional study abroad to this more cohesive program for international study to these overseas sites and, of course, a substantial international population on our own campus,” says Lohmann, an industrial and systems engineer. “What we need now is to get our arms around all this and develop a more cohesive connection between all these activities.”

“We’re not quite there yet,” adds the vice provost, who talks purposefully about getting people to view Georgia Tech “as basically a multinational university, much as you would speak about a multinational corporation. When you think of IBM, you don’t think of any particular site location. We’re trying to articulate a vision for Georgia Tech… (so that) in 10, 15 years, when people hire our graduates, they might ask, ‘Well, where in Georgia Tech did you graduate from?’ They won’t necessarily assume Atlanta.” Instead, that student might have matriculated in classes taught by Georgia Tech professors in the university’s campus of long standing in Metz, France, or in facilities being created through academic partnerships in Singapore; Shanghai, China; Hyderabad, India; and other parts of the world. “What we’d like to do is to offer Georgia Tech’s education and research programs globally and the product you get is the same, no matter where you get it, anywhere in the world, just like buying a Coca Cola,” says Lohmann.

Clough emphasizes that to sustain international ventures like this, “there has to be a financial model that works.” David Parekh, deputy director of the Georgia Tech Research Institute and associate vice provost, made 15 trips to Ireland over two years in securing support from IDA Ireland, the Irish development agency, and corporate partners to open a research beachhead in Athlone, on the River Shannon in the center of Ireland. “At Davos, at the last World Economic Forum, Bertie Ahern, the Taoiseach (prime minister) of Ireland, spoke about Georgia Tech’s being an overt part of the country’s strategy for innovation,” says Parekh. Irish President Mary McAleese visited the Atlanta campus in April.

Nearly 1,000 a Year Study Abroad

Georgia Tech boasts that it makes study abroad possible for all majors. In 1993, 191 Tech students studied abroad. Now it sends five times that many, mostly on summer courses combining travel and study in a profusion of fields. “Given the kind of university Georgia Tech is, it’s remarkable that we have 34 percent of our students studying abroad,” said Howard A. Rollins, Jr., a psychology professor who as associate vice provost for international programs and director of the Office of International Education from 2003 to 2007 was also a principal architect of the International Plan.

The International Plan requires students to complete at least 26 weeks of study, internships, and research in another country and to demonstrate proficiency in a second language. To do so, they must pass an independent oral exam certified by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL); Georgia Tech picks up the $140 exam fee. Students also must take three courses examining international relations, global economics, and a specific country or region, followed by a capstone seminar designed to tie the coursework and international experiences together with the student’s major and future profession. Industrial design students in the College of Architecture, for instance, might design senior projects to European specifications and markets. Those who fulfill these requirements receive a special International Plan designation on their bachelor of science degree. “It’s a degree designator. It’s not something that Tech takes lightly,” says Jason Seletos, a program coordinator for the Office of International Education. “The last degree designator before this one was for co-op and that was done in 1912.”

Georgia Tech embraced the International Plan and allocated $3 million for its first five years—mostly for additional language instructors. It hopes to entice 300 students per class—12 percent to 15 percent of the student body—to sign onto the International Plan so that at least half the students graduate with an international experience under their belt (it was already at 30 percent). Georgia Tech remains a mainstay of cooperative education combining classroom and workplace experiences. Four hundred seniors each year earn the co-op designator on their Tech diplomas. The Cooperative Division was renamed the Division of Professional Practice in 2002 and now runs a work abroad program that helps students land internships and co-op positions outside the United States. Debbie D. Gulick, the assistant director, says, “We sent 32 students to work in 15 countries last year, and this year we have 46 students in 19 countries.”

‘Seditious’ Nature of the International Plan

William J. Long, chair of Tech’s Sam Nunn School of International Affairs, believes that “the seditious quality” of the International Plan will transform Georgia Tech. “When you have more students studying abroad, bringing back foreign ideas into the classroom, and raising questions about this wider world, the faculty here at Tenth Street on North Avenue are going to have to adapt to this thrust and become more international as well, and we’ll draw even more talented students,” says Long. The Sam Nunn School, founded in 1990 and named for the former Georgia senator, enrolls more than 360 undergraduates in international affairs and language majors. In 2008 it will offer a Ph.D. for the first time, with a special focus on science and technology in international affairs. “That’s our unique niche in international education,” says Long.

The Nunn School in 2005 produced the third Rhodes Scholar in Georgia Tech history: Jeremy Farris, of Bonaire, Georgia. During his years at Tech, he took summer courses taught by Associate Professor of International Affairs Kirk S. Bowman in Argentina and Cuba, traveled as a President’s Scholar to Guatemala and El Salvador over a third summer, and spent a full semester in England. At Leeds University “I studied classes that were not offered at Georgia Tech on political philosophy, Nietzsche, Husserl, Dostoevsky,” Farris wrote by e-mail from Oxford, where he is now working on a Ph.D. in political theory.

Bowman is also the faculty director for the International House, a dorm where 48 U.S. and international students live. The I-House, as it’s called, has become a magnet for internationally minded students, regardless of nationality. “It’s been very satisfying for me to see how happy the students are,” says Bowman. “They’re actually in a place where everyone is interested in trying different foods and going to foreign language films.”

‘Green’ Live Rock for the Georgia Aquarium

Bowman is currently working with biology professor Terry Snell and scientists from the University of the South Pacific and Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California to develop drugs from the coral reefs of Fiji. Bowman’s end of the project is to encourage Fijian villagers to plant synthetic rock rather than collecting the natural rock from coral reefs for their livelihoods. The Georgia Aquarium, Atlanta’s newest tourist attraction, purchased five tons of the “green” live rock, which in the sea attracts the same colorful organisms as the real stuff. Bowman says the culture at Georgia Tech encourages far-flung projects like this. “Interdisciplinary research is a nice buzzword at most universities, but there are no incentives to actually do it. Here, because applied research is so valued, there are a lot of niches for interdisciplinary research and teaching,” says Bowman. “For a political scientist, I have all sorts of collaborative research opportunities with biologists, and chemists and engineers and what-not. It’s great.”

Encouraged by Molly Cochran, another associate professor in the Nunn School and director of undergraduate programs, Ashley Bliss, 21, of Marietta, Georgia, and Emily Pechar, 19, of Atlanta, both quickly signed up for the International Plan. Bliss, a junior majoring in economics and international affairs, spent a semester studying in her mother’s hometown of Monterrey, Mexico, living with a cousin and girlfriends she had known since childhood. She landed a job as an intern at CNN Español and spent this past summer studying in Argentina.

Pechar, a freshman international affairs and modern language major, foresees spending her junior year on Georgia Tech’s exchange with Sciences Po, the prestigious French political science institute in Paris. When she got an opportunity to attend an AIESEC student leadership conference in Morocco over spring break, the university picked up the conference fee and most of her plane ticket. “I don’t think schools without such an international mindset would have done something like that,” Pechar says.

Clough, raised in southern Georgia by parents who had not gone to college, says that with 80 percent of undergraduates in engineering and science and two-thirds from Georgia, some students still need to be convinced to fit study abroad into their busy schedules. But it is inarguable, he adds, that they need to graduate with a global view. “Even if they stay in this country—which is unlikely—during their careers, they are going to be impacted by this global economy,” says Clough. “They have to be able to speak to people with different accents. They have to be comfortable in that world and to appreciate it.”

Clough discovered his calling as a geotechnical and earthquake engineer in graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley. Civil engineering faculty there were drawn into that field after the 1964 Good Friday earthquake in Alaska and a major temblor struck Niigata, Japan. “When you get into that field, you’re immediately immersed in a global enterprise,” says Clough.

Birth of GT-Lorraine

Georgia Tech boasts that it is the only U.S. institution with a campus of its own in France: Georgia Tech Lorraine. Opened in 1990, it offers primarily graduate courses in electrical and computer engineering taught by Georgia Tech faculty as well as non-engineering courses taught by Tech faculty and adjuncts. It owes its existence to the vision of the longtime mayor of Metz, Jean-Marie Rausch, who came to the United States looking for a major technological university willing to establish a branch in Lorraine. “He said, ‘We are setting up a technology park in cow pastures outside of Metz. He was greeted here with open arms,” relates John R. McIntyre, the founding director of Georgia Tech’s Center for International Business Education and Research (CIBER). McIntyre, who was born in Lyons, France, to an American father and French mother, adds, “We’ve gotten more mileage out of it than we could have ever hoped.” The French partners provided bricks and mortar, including 50,000 square feet of classrooms, laboratories, research facilities, offices, and dorms. Visiting Georgia Tech faculty get apartments and cars. “When our faculty go there, they know where their children are going to go to school, they know where they are going to live. Normally when faculty go overseas, none of that stuff is known and it’s hard,” says Clough. More than 80 Georgia Tech faculty have spent a semester at GT-L, and the branch campus has awarded 800 graduate degrees.

Georgia Tech began sending undergraduates to Lorraine for summer classes in 1998 and now 160 sign up for that experience each summer. Students this year could choose from more than two dozen courses on topics from thermodynamics to international business. For graduate students and undergraduates alike, English is the mode of instruction. Georgia Tech grants dual master’s degrees with nine European partner institutions. “The French students call this the Atlanta campus,” Sheila Schulte, director of International Student & Scholar Services, says with a smile. Sophie Govetto, 26, a French graduate student in mechanical engineering, marvels at the breadth of courses offered on the main campus. “In GT-Lorraine you have to choose four classes out of six offered; you have restricted choice. Here you can choose from thousands. For us Europeans and especially French, that’s good. We’re not used to choosing our classes.”

Some of the best students produced by GT Lorraine return to Atlanta to pursue Ph.D.s, as Matthieu Bloch, 25, of Previssin, France, has done. The computer engineer, who works on cryptography, says, “It’s a different experience. The campus here is huge. Campus life in the U.S.—that’s something I wanted to experience. I really loved it. That’s why I decided to sign up for a Ph.D.” Bloch recently received a doctorate from his French university and expects to complete his Georgia Tech Ph.D. by year’s end.

A Two-Way Street

His mentor, Steven W. McLaughlin, deputy director of Georgia Tech-Lorraine, says, “We bring students to the campuses of our partners who would not have ended up in Metz if George Tech weren’t there. They help us, we help them. It’s a two-way street.” For any institution seeking to emulate what Georgia Tech has done, the lesson is “to keep the long term in mind,” says McLaughlin. “Even though we’ve been doing this for years, it’s still a lot of hard work to build and sustain our program. You need to find a strategic partner willing to invest not just for two or three or five years but for a long time, maybe forever. We have that kind of a partner.”

After Lorraine, the single most popular destination for Georgia Tech students is the university’s summer program at Oxford University in England. “We take over Worcester College in Oxford every summer,” says Anderson D. Smith, Vice Provost for Undergraduate Studies & Academic Affairs. Some 150 Tech students spend six weeks at Oxford, and many spend an additional four weeks traveling with professors across the continent. “That is very popular,” says Smith, “but many of our students can’t afford the extra expense. We’ve got to make sure that every student who wants to study abroad can do so.” That will be one of the objectives in a new fundraising drive. The University System of Georgia allows out-of-state students who study abroad to pay in-state tuition plus $250. Douglas B. Williams, associate chair for undergraduate affairs in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, says, “I tell our out-of-state students all the time that it’s cheaper to go to Metz for the summer than to stay in Atlanta and take classes here.”

Logistics Goes Global

Georgia Tech’s Stuart School of Industrial and Systems Engineering (ISyE) and its Supply Chain & Logistics Institute have long been ranked number 1 in that field. Harvey M. Donaldson, the managing director, says, “We did not start off to have an international program; we simply were interested in logistics. But we can’t do our business in just the 48 states of the continental United States. As supply chains expanded, the domain where we applied our technologies and expertise became global.” Through an alliance with the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the Singapore Economic Development Board, it created the Logistics Institute-Asia Pacific, which offers master’s degrees, conducts research, and convenes conferences. Companies such as DHL, the international shipping giant, pay the tuition of graduate students from the island nation and other countries in Asia in exchange for a three-year work commitment. “Between 15 and 30 students are enrolled each year in the 18-month program,” says Donaldson. “They complete a semester at the National University of Singapore, come here for the spring and a May-mester, then do an internship back in Singapore before they receive dual degrees.”

Graduate student Ke Yao Liu, 25, of Hebei, China, lauded a seminar in Atlanta led by Chen Zhou, an associate professor, that took students out to the Atlanta distribution centers for UPS and FedEx and the hub of the Norfolk Southern railroad’s operations. “We learned a lot through this class,” says Liu. “In Georgia Tech, what we learn is practical. We address industrial problems directly. We see how it works and we can match the concept and theory to practical issues.”

Another logistics graduate student, Magdalene Chua, 28, of Singapore, was equally enthusiastic. “When you speak to the people in the logistics industry in Singapore about Georgia Tech, they say, ‘Oh, you are going to Georgia Tech. Wow!’” she says.

Hiroki Muraoka, 24, of Saitama, Japan, who was studying in the Global Logistics Scholars dual degree program, says, “In Japan I could just remember the theory. Here I have to understand and apply it.”

Professor Zhou also leads an 11-week summer study abroad program that takes undergraduates to Singapore and Beijing to study manufacturing, logistics, and modern Asian history. Two dozen Georgia Tech engineers are joined by NUS students in Singapore and by students from Tsinghua University in Beijing. “With a program like this, there’s no way you can force anyone to go. They can take all the courses here. The only thing you can do is take advantage of their natural interest to go to that part of the world,” says Zhou.

The students also are learning that, as Chip White, chair of ISyE , says, “the people who design routes now are no longer just in Atlanta. They can be in Shanghai and Singapore and all over. Innovation in this industry is globalizing, too.”

Expanding Partnerships Around the World

Clough, a former dean of engineering at Virginia Tech, says that when he became president, he recognized a need for Georgia Tech to establish in Asia an academic base similar to Georgia Tech Lorraine. “Singapore turned out to be a good place to start,” he says. Tech also offers dual degrees with prestigious Shanghai Jiao Tong University, where it now has offices and a plaque on the wall reading “Georgia Tech Shanghai.” Georgia Tech Research Institute opened its branch in Athlone, Ireland, in 2005 and this spring Provost Gary Schuster signed an agreement to explore the potential to open a Georgia Tech campus in Hyderabad, India. Georgia Tech is also in talks with potential partners in South Korea and Latin America. “A week doesn’t go by that we don’t have someone contacting us about a joint degree program, a joint research program (or) some kind of larger connection to us,” says Clough. “Everybody’s looking to partner up.”

Teaching Grad Students Not to Stand Up

In a similar vein, Schuster, a biochemist whose predecessor, Jean-Lou Chameau, was tapped by Cal Tech to become its president in 2006, offers this prediction: “We are in an era now in which networks are being established and relationships built. We are going to find partnerships that work and partnerships that don’t; we’ll support the ones that do—and say goodbye to the ones that don’t.”

Schuster early in his career coauthored a seminal study on the bioluminescence of the firefly. Today he works on molecules that bind and cut DNA when irradiated with light. A steady stream of postdoctoral fellows from India works in his lab, and Schuster says the first thing he teaches them is not to stand up when he walks in. “I don’t want them deferring to me because of my position. I want them to challenge me and my ideas,” he says. “That’s the great strength of the American research university. It’s not a culture of status.”

The entire world now recognizes that research universities are “not only places for deep thought and discovery, but engines of economic development,” adds Schuster. In establishing these “remote operations” in other parts of the world, “we have to make sure to be true to ourselves. What we have to export is not only our way of teaching but our culture.”

‘Not Your Traditional Language Program’

Although language study is not required at Georgia Tech and there is no stand-alone language major, enrollment in language classes has doubled in the past five years to more than 4,400 students. Junior Eddie D. Lott, an industrial and systems engineering major, spent fall 2005 studying in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and enjoyed the experience so much he was headed off this fall for a whole year of study and work in Valencia, Spain. He credits Tech’s Lorie Johns Paulez, the semester study abroad adviser, with encouraging him to apply for as many study abroad scholarships as possible. He won several, including a federal, $5,000 Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship. Lott, an Atlanta native, says, “A lot of people come to me and say, ‘Study abroad is too expensive.’ I say, ‘Put yourself in the mix. There really are a lot of scholarships out there.”

The School of Modern Languages within the Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts (which also houses the Nunn School) offers classes in Spanish, German, French, Russian, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Arabic. Phil McKnight, the chair of modern languages, says, “We are not your traditional language program here at all. This school has a very interdisciplinary and pragmatic approach. We still do literature and culture, but that’s just a part of the curriculum.” Half the students are engineers. “One of our signature programs—if not the signature program—is our series of summer intensive language programs called Language for Business and Technology” (LBAT), says McKnight, a professor of German. These summer immersion programs in China, France, Germany, Japan, Mexico, and Spain offer six to eight weeks of study abroad that combine classroom lessons in business, culture, and technology with field work, cultural events, excursions, and visits to local businesses. Eighty to 90 students customarily head off with Georgia Tech professors to Toulouse, France (home to Airbus); Weimar, Germany; Tokyo and Fukuoka, Japan; Mexico City, Mexico; Madrid, Spain; and Shanghai, China. A U.S. Department of Education Title VI grant supported the creation of the LBAT courses in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Russian. Mike Schmidt, 24, of New Orleans, a graduate student in mechanical engineering, did internships with Bosch and Siemens and spent a full semester in regular classes at Technical University Munich (TUM). He had no problem writing business reports in German. “My experience abroad has gotten me a lot more opportunities than anything else,” says Schmidt.

Kendall Chuang, 24, a graduate student in electrical and computer engineering, minored in East Asian studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and spent a year at Konan University in Kobe. He returned to Japan as part of Georgia Tech’s cooperative education program to spend six months interning at NTT’s research center, where he worked alongside engineers and scientists twice his age. “I really didn’t expect engineers (at Georgia Tech) to be so interested in learning about other cultures and other languages,” he says.

Charles L. Liotta, who has overseen Georgia Tech’s $345 million research enterprise as vice provost for research and dean of graduate studies, says that the university’s “global vision” will serve it well in the increasingly competitive arena of the twenty-first century. “I can describe the culture of Georgia Tech in the following way: we believe that the real world problems exist at the interface between different disciplines, and that interdisciplinary research is the way to define a problem, to address it and to solve it,” says Liotta, a chemist who joined the faculty 42 years ago. The $1.2 billion in new buildings constructed on Clough’s watch “has really fostered that culture,” adds the Brooklyn-born Liotta. “We put many disciplines in one building, and in many cases not just in the same building but in the same laboratory so we can lower the barriers and foster that interdisciplinary research.”

How Long Does It Take?

Jack Lohmann, the vice provost for institutional development, sees another challenge for all of U.S. higher education in the international arena. “We need to do a lot more scholarly work in understanding and getting our arms around what it means to be globally competent. At the moment we’re working a lot on seasoned wisdom as opposed to evidence-based research,” he says.

“We need to start asking the questions: How long does a student have to be overseas, six weeks, six months, six years? Does it matter what kind of experience they have? Does a work experience have a bigger impact than doing study abroad? What’s the impact of a second language? At the moment, we cannot give cogent answers to these questions.” Georgia Tech’s Office of Assessment already has launched a longitudinal study to shed light on the issue, and the growing numbers of students’ signing up for the International Plan should provide ample data for Lohmann and his colleagues to ponder.

Georgia Institute of Technology

2007 Comprehensive Elon University

Elon University has gone on an extra-ordinary journey in the past 15 years, transforming itself from a regional college into a comprehensive university with a national presence that receives far more applicants than it can accept from across the country. The beautiful 575-acre campus near Burlington, North Carolina, with dogwoods, magnolias, cherries, redbuds, and oaks—Elon means oak in Hebrew—is designated a botanical garden, and Elon has mastered the knack of building in a Georgian style that makes new dorms and classroom edifices look like they have been nestled in those trees for eons.

Adding to the curbside appeal is Elon’s reputation as an institution where students become deeply engaged in community service, and where a large majority studies abroad. So deeply is study abroad engrained in the culture at Elon that even the custodial and administrative staff has the opportunity to see London in January, when the flats reserved for Elon students in the fall and spring would otherwise be empty.

Elon provides each student—and, if they so request, prospective employers and graduate schools—not only course grades, but a second, formal transcript on their participation in five “Elon Experiences,” namely: leadership, service, internships, study abroad, and undergraduate research.

Elon cemented its reputation for civic engagement by perennially emerging among the high scorers on the National Survey of Student Engagement. Elon also was one of the 10 original campuses that em-braced Project Pericles, a national effort to promote good citizenship under the aegis of philanthropist Eugene Lang and his foundation. Not only did 71 percent of the Class of 2007 study abroad, but 80 percent completed an internship and 91 percent engaged in volunteer service.

Elon engineered its rise with strong administrative and faculty leadership, a passion for strategic planning, and a knack for stretching limited dollars. (These gains have not gone unnoticed: a 2004 book authored by George Keller from Johns Hopkins University Press, Transforming a College: The Story of a Little-Known College’s Strategic Climb to National Distinction, examines Elon’s rise to a top regional university.) Elon is a place that prides itself on congeniality, down to the “College Coffee” on Tuesday mornings when classes and work stop for 40 minutes while students, faculty, and staff gather outside the main campus building for coffee, donuts, and conversation. Faculty have embraced study abroadwith gusto. Each year, more than 50 faculty memberslead study abroad programs, most on short-term courses offeredin the winter and summer. A Study Abroad Committee, a standing committee of faculty that includes two student members, passes judgment on each program, and faculty say their participation in study abroad, including not only course development and teaching but scholarship as well, is valued as a critical part of their professional development.

Clearly, international studies and global awareness have played a large role in the creation of this new Elon. “Two or three decades ago Elon served first-generation college students,” says President Leo M. Lambert. Today, 80 percent of the parents are college graduates and more than a third boast graduate degrees as well. “These parents are aware how small the world is getting and how important it is for their student to experience that world more broadly through their Elon education,” adds Lambert.

Lambert’s predecessor, J. Fred Young, president from 1973 through 1998, set the institution on this course and nurtured the study abroad programs. Young, a former school superintendent, created an organization that continues to place teachers from other countries in North Carolina public schools. He personally recruited one of those exchange teachers, Sylvia Muñoz of San Jose, Costa Rica, to come to Elon to open El Centro de Español—the Spanish Center—to provide Spanish language and cultural lessons in an informal setting to students, faculty, and staff alike. Now ensconced in remodeled Carlton Building next to the Isabella Cannon Centre for International Studies, El Centro bustles with activities day and night.

Isabella Cannon Shows the Way

At his 1999 installation, Lambert announced a landmark $1 million gift from Isabella Cannon, a 1924 Elon alumna, that gave international studies a showcase home at the heart of campus, overlooking Scott Plaza and Fonville Fountain. Cannon, born in Scotland in 1904, was a librarian, civic activist, and globe-trotter who in 1977, at age 73, campaigned as “a little old lady in tennis shoes” to unseat the mayor of Raleigh. A diplomat’s wife, she had lived in China, Iraq, and Liberia before concentrating her energy on opening parks and improving life in North Carolina’s capital. As commencement speaker in 2000, the diminutive Cannon reminded Elon graduates that collectively they had “a grand total of more than 50,000 years to make this a better world.” She made another major gift that allowed Elon to build the Isabella Cannon International Studies Pavilion, which houses 11 international and 11 U.S. students and is one of several living-learning communities in the university’s Academic Village, modeled after Thomas Jefferson’s design for the University of Virginia. Cannon died in 2002 at age 97, six months before the dedication of the new Isabella Cannon Centre for International Studies, with Benazir Bhutto, the former prime minister of Pakistan, as principal speaker.

Elon changed its name from Elon College to Elon University in 2001—the town that had grown up around the college had to change its name, too, from Elon College, North Carolina to plain Elon—and, underscoring that status, opened the Elon University School of Law in nearby Greensboro in August 2006. Elon already offered graduate degrees in business, education, and physical therapy. On Lambert’s watch, the full-time faculty has grown from 192 in 1999 to 291 in 2006.

Elon charges lower tuition than many of the universities with which it competes for students, but it does not discount that “sticker price” to woo students. Its endowment stands at $70 million, but Elon’s leaders hope to boost it by $100 million in a five-year campaign now underway.

Elon’s growth over the past decade was fueled by admitting more students, from 3,500 in 1995 to more than 5,200 today. “We’ve benefited tremendously from our location and being in this great mecca of higher education in North Carolina,” says Lambert, a former education professor and associate dean at Syracuse University who founded an innovative program there to hone the teaching skills of future professors. “Growth has fueled quality at Elon; there’s absolutely no doubt about it,” Lambert says. “But we can’t continue to growand still be the intimate kind of community Elon is right now.”

Studying Abroad in January

Elon has built its study abroad reputation largely around month-long winter-term courses offered in the middle of its 4-1-4 calendar. It began with a single January course in London in 1969. Elon now offers approximately 30 such winter-term study abroad courses. In 1985 Elon began sending students and a professor to London for a full semester; in 2006 the university added a faculty-led semester in San Jose, Costa Rica, that combines Spanish classes with courses taught in English in marketing, the politics of Central America, and environmental issues.

Elon also offers students opportunities to enroll in 32 affiliate and exchange programs as well as seven Elon summer study abroad courses. Increasingly, Elon also is placing students in international internships, co-ops and other educational experiences, and Laurence Basirico, dean of international programs, is scouting possibilities for new semester-long Elon programs in Europe and Asia. “We want to have one on each of the continents,” says Steven House, dean of Elon College, the College of Arts and Sciences.

These extensive off-campus programs are a costly undertaking for an institution on a tight budget. That they have grown so large is testament to the importance the university places in international education. “When you have 60 students studying abroad for a semester in Italy, Elon sends all of their tuition funds to the Italian school and loses use of these funds for the main campus. It’s a big expense,” says Provost Gerald Francis, who joined the faculty in 1974 after earning his Ph.D. in mathematics at Virginia Tech. Francis’s 24-year tenure as academic dean and provost spans the Young and Lambert eras. His role in Elon’s metamorphosis was pivotal.

From Custodians to Faculty, Everyone Gets a Chance to Go Abroad

Francis also has been a champion of finding creative ways to help faculty and staff experience travel abroad. Gerald Whittington, Elon’s vice president for business, finance, and technology, personally has led 300-plus Elon faculty and staff—from full professors to custodians—on more than a dozen London trips. Whittington sees a practical payoff to taking the staff to see the sights of London for themselves. “Our students are getting messages from above, below, and sideways that this is an important value of the institution and one that they ought to participate in. That’s why we do it,” says Whittington, who grew up in the great cities of Europe.

“Don’t think there is not self-interest in this. They are all part of the sales force,” agrees Francis. The provost even encourages Basirico to send a university staff member, when possible, with the faculty who lead the regular study abroad courses in January. If an Elon art historian takes students on a fast-paced program to Italy, “it really helps if you have somebody to help keep up with the busses and hotels,” reasons Francis. “Librarians, purchasing agents, the registrar, or people in student life can (do that) to help the program run smoothly. And that makes them part of the international campus here.”

Courses with Few Prerequisites

Last January, Elon faculty led students to Australia, Barbados, Brazil, China, Costa Rica, France, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Guatemala, Ireland, Italy, New Zealand, Peru, the Philippines, and beyond.

While students typically pay from $2,800 to $5,500 for travel, lodging, and other expenses for the winter study abroad courses, they are charged no extra tuition; that is bundled into the fall semester tuition. Courses also are offered back on campus for students who cannot participate in the study abroad. Traditionally, most of the winter-term study abroad programs are 200-level courses with few prerequisites. That was done intentionally so students wouldn’t be precluded from signing up, says Basirico. Thomas K. Tiemann, an economics professor who holds an endowed chair, says, “There’s a big range of study abroad opportunities here, depending on the students’ experiences, attitudes and how brave they are.”

Increasingly, these courses are gaining rigor. Some were challenging from the start, such as “Field Biology in Belize,” in which students learn about rainforest ecology and explore a coastal reef. The course is open to non science majors, but since it counts as a lab elective for the many biology majors who sign up, “I want it to be challenging,” says biology professor Nancy E. Harris. “They may have had botany, zoology, and maybe even ecology, but when they get there, they are blown away. It’s truly an eye-opening experience.” Students start each day at a wildlife preserve in Belize’s Rio Bravo bird-watching at 6:30 a.m., followed by lectures and field observations. Students keep cultural and scientific journals, take exams and lab practicals. It’s a real science class but with a huge dose of cultural and biological reality. “The itinerary reflects the rigor. There’s very little free time,” says Harris, who also is associate dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, which is called Elon College. “There are howler monkeys overhead, jaguar in the forests, poisonous snakes under the decks, (and) bats in the bathroom. It’s cool.” At night students go out with flashlights, poke sticks in holes, and “play the game of who will let the tarantula walk over their head,” says Harris. During the marine biology half of the class, the students go snorkeling along the coral reefs in the azure Caribbean off Ambergris Caye, but even there they have lectures, tests, and field reports to complete. A USA Today reporter who accompanied the class in January 2004 noted, “One of their final exams, a ‘fish and coral practical,’ is conducted under water, using waterproof paper.”

“Study abroad has tentacles…”

Faculty new to Elon often are surprised at how quickly the opportunity arises to teach in another country. Vic Costello, associate professor of communications, says, “It seems like the whole institution buys into it. I’m living proof. Two years after I came in, I was leading a class to Europe.” Demand was strong for Costello’s course, Gutenberg, Reformation and Revolution: Media’s Impact on Western Society, which took students to Mainz, Germany, the birthplace of the printing press, and ended in Geneva, Switzerland, where the Internet was born at the CERN Institute. “Study abroad has tentacles that go throughout the campus. It is fully integrated with the culture of the school,” says Costello, who chairs the Study Abroad Committee.

Vice President G. Smith Jackson, the longtime dean of students and coordinator of the Elon Experiences, says, “Students come to Elon because of our active, engaged approach to learning, and study abroad is at the top of that.” Jackson describes the dynamic as a “collision of powerful factors: students and parents who want this type of education, an administration that supports it, and faculty who understand the power of that pedagogy.”

Elon awards $50,000 in scholarships for study abroad each year. Honors students and Elon Fellows automatically receive a $750 travel grant as part of their awards. “When we spend a dollar around here we like to say we are getting two or three things done,” says Lambert. “An example is the way we top off certain scholarships to emphasize the importance of internationalization and global citizenship.”

Good Timing for an International Plan

A decade ago, when winter study abroad started taking off, the international program was still operating out of a crowded ground-floor office in the Alamance Building. Bill Rich, then the dean, put together an ambitious blueprint for expanding the size, staff, and reach of the international programs office. A year later, when Isabella Cannon presented her $1 million gift, it became a reality. Rich, an emeritus professor of religious studies, retired in 2004, but still leads a winter-term trip to Athens and Thessalonica to study the art, architecture, mythology, and religion of ancient Greece. Some of these winter courses are so popular that students are left with a second or third choice. It’s a far cry from the early days when “we would stand in the cafeteria lines to recruit students for study abroad,” Rich says.

Education Internships in Costa Rica

Basirico, who is also a sociology professor, returned from a 2004 trip to Costa Rica and asked F. Gerald Dillashaw, dean of the School of Education, if he’d be interested in sending education majors to San Jose for a semester to intern in Costa Rican classrooms. The School of Education already was sending upward of 20 sophomores to assist in London schools each spring. In Costa Rica, of course, there would be the added complexity of working in Spanish. Immediately, “everyone on our advisory committee was in favor of the idea,” says Janice L. Richardson, an associate professor of mathematics who directs the North Carolina Teaching Fellows Program at Elon. The Teaching Fellows Program is a scholarship program jointly funded by the state and the university that provides $13,000-a-year scholarships for 25 students from North Carolina who agree to spend four years teaching in North Carolina schools. Both Dillashaw and Richardson traveled to Costa Rica to lay the groundwork, and seven education majors spent this past spring as teacher aides in San Jose, living with local families and also taking classes of their own. On a recent visit, one Elon sophomore told Richardson, “Now I know what it’s like to be a Spanish-speaking student walking into an English classroom and not understanding the language.”

Elon has another steady connection with Costa Rica. As a reward for faculty and staff who participate in the conversational Spanish classes and cultural activities at El Centro de Español, Sylvia Muñoz escorts a dozen or more faculty and staff to her homeland each May. Participants are charged just $400. And El Centro offers a travel perk for students, too, who show up faithfully for its conversations, cooking classes, rumba lessons, movie nights, and festivals like Día de los Muertos: Once they log 140 hours, “they get a free plane ticket to any Spanish-speaking country. A lot use it to study abroad,” says Muñoz. The ticket is funded through the provost’s office.

Freshman Seminar on ‘Global Experience’

The curriculum at Elon sends an early signal to freshmen about the importance the university places on internationalization. “Right off the bat we expose students to the idea that theirs is not the only world and that there are other places and people worth studying,” says Janet Warman, an English professor who directs the General Studies program. Freshmen must take a seminar on The Global Experience taught by faculty from every department that explores such issues as human rights abuses and environmental responsibility. With a limit of 25 students per section, the seminar dates back to a 1994 revision of the core curriculum. Warman, who received Elon’s top teaching award in 2004, says, “Early on, there was a lot of resistance. Students didn’t seem to understand why we were studying the things we were studying. Now they are much more receptive.” Two years ago, when former Sudanese slave Francis Bok lectured about his autobiography, Escape From Slavery, “the students flocked around him to hear more of his story and ask how they could take action,” Warman says. The General Studies program does not end with freshman year. As juniors or seniors, students must take advanced interdisciplinary seminars. Elon reinstated a language requirement three years ago, and already the language faculty want to raise it. “A two-semester requirement is really quite minimal,” says Ernest Lunsford, a professor of Spanish. “We also would like to have more study abroad that incorporates serious language study.” Elon offers majors in Spanish and French and minors in Italian and German studies. Classes are also taught in Chinese, Japanese, and Arabic.

The only major other than languages that requires study abroad is international studies, which has surged in popularity. Laura Roselle, a political science professor, says, “In 1997 we had 12 majors. Right now we have 173. Each time we raised the requirements, we thought, ‘Uh-oh. Enrollments might suffer.’ But it has not slowed at all.” International studies, she says, appeals to the service-oriented students drawn to Elon. “They are looking for a place where service opportunities and volunteer activities are valued, and they find that here,” says Roselle. “The to-do list for Elon is to deepen the connections between the academics and those experiences.”

Project Pericles and AIDS in Namibia

Project Pericles, a national civic engagement initiative that Elon signed onto in 2002, also has had a decidedly international cast to its character. The first 29 Periclean Scholars in the Class of 2006 focused on the problem of HIV/AIDS in Namibia. Over three years, under the direction of sociology professor Tom Arcaro, the group produced a four-part documentary series that aired on public television in the region. The project brought to campus speakers from Namibia, including Anita Isaacs, an activist for those living with HIV. Arcaro, who was North Carolina’s Professor of the Year in 2006, also led several students and a campus video producer to Namibia to meet with AIDS activists and tape footage for the documentary series. Students packed 70-pound suitcases with textbooks, toys, school supplies, and clothing that they distributed to Namibian school children. Lambert called Arcaro’s stewardship of the program “the single most powerful, sustained, and globally influential act of teaching and mentoring I have (ever) witnessed.” As seniors, 11 Elon students journeyed to southern Africa to join Namibian university students at a Future Leaders Summit on HIV/AIDS. The Periclean Scholars in the Class of 2007 tackled the problem of pediatric malnutrition in Honduras, and subsequent classes also have chosen an international focus for their work.

If there is any anomaly to this pervasive international culture, it is that fewer than 2 percent of Elon students are international. International enrollments have grown over the past decade from 40 to 89, and the university is eager to attract more. To date, its efforts to do so have been constrained by the limited availability of financial aid.

John Keegan, director of international admissions and associate director of admissions, travels the world recruiting students, and exchanges dozens of e-mails on a daily basis with prospects and their parents. “We would love to enroll 100 more international students,” says Keegan, a 1996 Elon alumnus. “Every day the international students on campus ask me, ‘Who else is coming from my country? Who else is coming from Panama? Who else is coming from Singapore?’ They are just as into it as we are.”

A Personal Touch

The personable Keegan is a persuasive salesman. Chae Kim, 20, a sophomore accounting major from Seoul, South Korea, and her parents got the full treatment when they pulled into Elon on a spring break trip after she spent a year in Jackson, Mississippi, as a high school exchange student. “He was very welcoming. He basically told my parents he would look after me while I was here,” said Kim. She found herself one of only two Korean students on campus that first semester, but that did not bother her. “I just feel obligated to step out more and represent who I am more because numbers-wise, there aren’t many of us,” said Kim, who interned for PricewaterhouseCoopers in Seoul this past summer.

Susan C. Klopman, vice president of admissions and financial planning, says stories like Chae Kim’s are “what has made Elon admissions and enrollment successful. We have been fortunate enough to really make connections with so many of our students. It’s getting harder with the proliferation of applications, but a personal relationship is critical for international students. To whom are they entrusting this child? What’s the nature of this school and this place? When they meet John, the trust level just goes sky high. He represents the Elon community so well.”

Another international student, Kira Tippenhauer, 21, a sophomore originally from Port-au-Prince, Haiti, says Elon’s size was just right. “I did not want to go to a huge school where I would be just a number,” says Tippenhauer, who heard of Elon through a family friend in Michigan who knew John Keegan’s sister. “I love it here,” says Tippenhauer. “There are not that many international students, but still there are students from 45 different countries. That means 45 countries in the world know about Elon and have parents who decided to send their kids to Elon.”

Munoz, the El Centro director, says, “What’s nice about the numbers we have now is that we stand out. People notice us. They really take us as part of their families. My supervisor, Lela Faye Rich (associate dean for academic advising) is like a mother for all international faculty. If you want to be recognized or known, it’s very easy.”

They also don’t have to worry about getting to or from the airport, 45 minutes away. “We pick them up, we drop them off at the airport. That’s any time that they ask for it,” says François Masuka, director of International Student and Faculty Scholar Services. “We do things I don’t think many schools do. The environment is a friendly, brotherly, sisterly type of environment. We cultivate that. You’ve got to hold more hands here.” Masuka, who hails from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and earned a master’s degree at the School for International Studies in Vermont, worked at the University of Virginia and Texas Tech University previously.

Stepping Up Exchanges

Elon hopes to bring more international students to campus by stepping up exchanges. Monica Pagano, assistant dean of international programs, says, “When I got here (in 2003), there were two exchanges. Now we have 14. It’s exciting.” The Argentinian-born Pagano is an authority on service learning. She returned in spring 2007 from the Dominican Republic, where she’d gone to expand opportunities for students to volunteer over spring break. So pleased were the parents of one 2006 Elon graduate with the service-learning projects that took their daughter to Guatemala and Tibet, that they gave the university $250,000 to fund international service-learning scholarships.

Many students who come for short stays are placed in the Isabella Cannon International Studies Pavilion with the domestic and international students living there for the full year. “It’s great to constantly have that flow of culture coming through,” says Ayesha Delpish, an assistant professor of mathematics who is the resident faculty member. Elon is hosting 20 exchange students in fall 2007, more than ever before. Nancy Midgette, associate provost, observes, “Now it’s our job to encourage our (domestic) students to be the other half of these exchanges. They work best when you have people going in both directions.”

Both Lambert and Basirico believe that the university will need more staff and resources to move its international education programs to the next level. With so many faculty leading study abroad courses, Basirico says, “The next step for us is to become a leader in terms of quality of programs and a leader in research on the pedagogy of study abroad.”

Lambert says, “There are times when you can’t just keep moving along the same trajectory. You’ve got to make a leap in terms of the resources you commit to a particular program.” Elon’s infrastructure for managing international programs was “built like everything else at Elon––by bootstrapping it and making it incrementally better and better. But after a period of years, you need to regroup, reorganize, and make new investments to take the program to the next level.”

Elon University

2007 Comprehensive Calvin College

The Dutch immigrants who settled in western Michigan in the mid-nineteenth century brought not only their culture and Reformed Protestant faith, but a strong interest in establishing schools to impart their principles and religion to the next generation. “Onze school for onze kinderen (our school for our children) was the operating description of both the college and the Christian day schools that they established,” according to a history of Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Calvin, one of the largest and most academically rigorous Christian colleges, remains firmly in the Christian Reformed fold. But Calvin is no longer onze school for onze kinderen. Fewer than half Calvin’s 4,200 undergraduates belong to the Christian Reformed Church. Ten percent are minorities, and there are more than 320 international students from five dozen countries. The majority of international students receive more than $10,000 a year in financial aid.